Civilization

Princeton Conference Celebrates UDHR’s 75th Birthday

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) turns 75 this month, and Princeton University recently held a two-day celebration of that.

PRINCETON—Events around the globe have cast a shadow over human rights and the great post-World War II project to rally the world’s peoples and nations to protect them. Although the gravest violations occur far away, Americans, whose constitutional government is founded on citizens’ unalienable rights – the rights inherent in all human beings – cannot easily remain indifferent when human rights are under assault. Amid political turmoil abroad and widespread intellectual confusion at home, renewing appreciation of human rights and their proper place in democratic self-government and responsible foreign policy is for the United States a vital act of democratic self-government and responsible foreign policy.

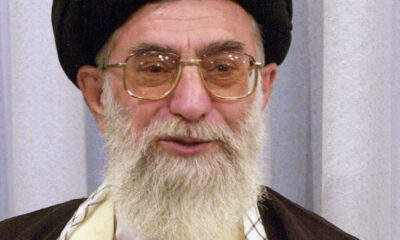

Authoritarian powers have been ramping up their assaults on human rights. In the Middle East two months ago, the Islamic Republic of Iran’s proxy Hamas massacred more than 1,200, mostly civilians, in Israel, while seeking to ignite a multi-front regional war of annihilation against the Jewish state. In Europe for almost two years, Vladimir Putin’s Russia has sought to conquer the sovereign state of Ukraine. And in the Indo-Pacific, the Chinese Communist Party maintains a repressive dictatorship at home while militarizing the South China Sea, threatening to seize Taiwan, and using China’s enormous economic clout to undercut freedom and democracy among nations and tilt the international order toward authoritarianism.

Meanwhile, confusion about, and disparagement of, human rights proliferate in the United States and in many of the West’s liberal democracies. Fashionable intellectual schools reduce human rights to mere ideology. Progressives invoke universal principles and commandeer human rights organizations to advance partisan political agendas. In reaction, many conservatives have fallen into the trap of repudiating human rights altogether as a legitimate standard of domestic politics and of the conduct of nations on the grounds that the appeal to universal principles can only serve as an excuse to pursue politics by other means.

In the face of these daunting headwinds – and almost exactly 75 years to the day after the United States joined 47 other nations at the United Nations to adopt the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (none voted against the UDHR, eight abstained, two did not vote) – a two-day conference held last week at Princeton University gathered approximately 40 religious leaders and scholars from around the world to reaffirm the power of human rights to unite peoples and nations. Princeton’s James Madison Program in American Ideals and Institutions cohosted “The Future of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights” with Nahdlatul Ulama, headquartered in Indonesia and, with around 100,000,000 members, the world’s largest independent Muslim organization; the Center for Shared Civilizational Values, which works closely with NU; and the G20 Religion Forum (R20), for which the Center for Shared Civilizational Values serves as a permanent secretariat. The conference aimed to build a “global consensus” that the UDHR embodies assumptions, principles, and goals that, consistent with the best in their own traditions, the world’s peoples and nations “should strive to fulfill.”

The opening dinner on Dec. 13 featured three inspiring keynote addresses. The three distinguished speakers from three far-flung regions – the United States, the Indo-Pacific, and Africa – described with sobriety and grace the daunting task.

Mary Ann Glendon, an emeritus law professor at Harvard – and chair of the U.S. State Department’s Commission on Unalienable Rights established in 2019 by then-Secretary of State Mike Pompeo (I served as the commission’s executive secretary) – argued that the UDHR’s history supplies reasons to believe that its core principles can be reclaimed and revitalized. She recalled the UDHR’s powerful impact on “the great grassroots movements that hastened the demise of colonialism, brought down apartheid in South Africa, and helped to topple the seemingly indestructible totalitarian regimes in Eastern Europe.” Men and women of faith played a crucial role in the advancement of human rights in the 20thcentury, she also noted, and expressed confidence that in the 21st century, members of diverse religions could again rise to the occasion. And as they did in 1945 in insisting on including the protection of human rights among the UN’s purposes, nations of lesser influence may in the 2020s again band together because they grasp “that without commitment to a few basic principles, nothing is left but the will of the stronger.”

Pak Yahya, General Chairman, Nahdlatul Ulama Central Board, made a powerful case that Muslims are not only permitted, but for religious reasons ought, to affirm the UDHR’s principles, beginning with Article 1: “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights.” Islam’s teaching that “peace, security, and stability in international relations are only possible if there is justice, and justice is only possible if the equal rights and dignity of all parties are guaranteed” dates to the 7th-century Medina Charter, he stated. After the horrors of the 20th century – two world wars, the Cold War, and the threat of nuclear conflagration – an open, secure, and stable international order grounded in human rights became not only a practical requirement for the peoples and nations of the world but also, in his view, a religious imperative for Islam.

“The very scope of the multiple crises facing humanity offers a compelling logic for people of goodwill of every faith and nation to cooperate in addressing these challenges,” observed Pak Yahya. “One essential step is to bring our religious teachings into alignment with the international consensus that emerged after the Second World War and mobilize our respective communities to build a more just and harmonious world order, founded upon respect for the equal rights and dignity of every human being.”

In the final keynote address, Most Rev. Dr. Henry C. Ndukuba, Primate of the Anglican Church of Nigeria, called attention both to egregious violations of human rights in Africa and to human rights’ enduring promise. Betraying the UDHR’s “original noble ideals,” he argued, Western governments and international organizations have invoked human rights “to indulge in, teach, and advocate cultural ideas and practices which are incompatible with the religious faiths and ethics of other people.” At the same time, Boko Haram, among the world’s deadliest jihadist organizations, along with other jihadists, have turned Nigeria into what may be “the deadliest place to be a Christian.”

However, far from seeing the UDHR’s principles as discredited, Ndukuba offered recommendations for making progress toward realizing them. Instead of promoting in Africa its progressive sexual mores as human rights imperatives, he advised, Western powers should join with nations around the world and the UN to protect Christians in Nigeria from Muslim extremism. Leaders of diverse religions must overtly embrace toleration, which will require a broad-based effort to reinterpret “as ungodly, inhuman, and outdated” sacred texts that “contain permission to kill, maim, kidnap, rape and enslave other people.” And the principle that religious freedom is a religious imperative should be adopted as a staple of education.

The conference sessions amplified and refined the keynote speakers’ observations, admonitions, and exhortations. Participants examined the process by which fundamental religious beliefs, enduring truths, and changing circumstances can be brought to bear to reinterpret and reform religious teachings that encourage hatred, supremacism, and violence. We explored the shared convictions, none more fundamental than the belief in human dignity expressed in equality of rights, that authorize members of different faiths to treat each other with respect. We considered the distinctive moral, philosophical, and spiritual resources that enable diverse religions to converge in affirming universal rights and duties while remaining faithful to their traditions. And we recognized that for the UDHR to serve, as its preamble states, as a “common standard of achievement for all peoples and all nations,” men and women of good will and understanding must“strive by teaching and education to promote respect for these rights and freedoms.”

During the conference discussions, Mary Ann Glendon commented that 75 years ago the UDHR achieved an imperfect but impressive transcultural consensus. Thanks in no small measure to the far-sighted leadership of Nahdlatul Ulama and the Center for Shared Civilizational Values, the UDHR may again imperfectly but impressively capture the shared convictions of the world’s peoples and nations.

This article was originally published by RealClearPolitics and made available via RealClearWire.

Peter Berkowitz is the Tad and Dianne Taube senior fellow at the Hoover Institution, Stanford University. From 2019 to 2021, he served as director of the Policy Planning Staff at the U.S. State Department.

-

Civilization3 days ago

Civilization3 days agoWhy Europe Shouldn’t Be Upset at Trump’s Venezuelan Actions

-

Executive4 days ago

Executive4 days agoHow Relaxed COVID-Era Rules Fueled Minnesota’s Biggest Scam

-

Christianity Today3 days ago

Christianity Today3 days agoSurprising Revival: Gen Z Men & Highly Educated Lead Return to Religion

-

Civilization4 days ago

Civilization4 days agoThe End of Purple States and Competitive Districts

-

Executive4 days ago

Executive4 days agoWaste of the Day: Can You Hear Me Now?

-

Executive5 days ago

Executive5 days agoWaste of the Day: States Spent Welfare in “Crazy Ways”

-

Civilization1 day ago

Civilization1 day agoWhy Europe’s Institutional Status Quo is Now a Security Risk

-

Civilization2 days ago

Civilization2 days agoDeporting Censorship: US Targets UK Government Ally Over Free Speech