Executive

The Balancing Act of Immigration

President Joe Biden unveiled the most expansive immigration action in years last week, offering potential citizenship to hundreds of thousands of immigrants without legal status in the United States. The recent action is a counterbalance to Biden’s early-June crackdown on asylum at the U.S.-Mexico border.

Biden goes lax on immigration …

Biden announced that his administration will allow certain undocumented spouses of U.S. citizens to apply for permanent residency – and eventually citizenship – without first having to leave the country. The action could affect over half a million people and about 50,000 noncitizen children under age 21 whose parents are married to a U.S. citizen.

Biden pitched the new executive action as a “common-sense fix” to the “cumbersome” system that is already in place.

“Under the current process, undocumented spouses of citizens must go back to their home country, for example to Mexico, to fill out paperwork to obtain long-term legal status,” he explained. “They have to leave their families in America with no assurance that they will be allowed back in the United States. So they stay in America, but in the shadows, living in constant fear of deportation without the ability to legally work.”

… after first virtue-signaling with a phony “harsh” measure

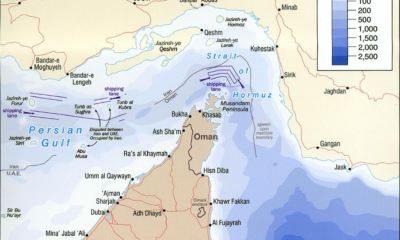

The move serves to lessen the blowback from another Biden administration executive action from early June, which prohibited entry into the United States of any noncitizen attempting to cross the southern border without going through a designated port of entry.

This harsher action relies on Section 212(f) of the Immigration and Nationality Act, a provision that allows the president to deny entry for migrants whose presence is deemed “detrimental” to national interest. It is set to remain in effect until the weekly average of daily illegal border crossings remains below 1,500 for two weeks straight – a level that has not been reached since the pandemic in 2020.

The American Civil Liberties Union and several pro-migrant groups filed a lawsuit shortly after the restrictive order was announced, challenging its legality. The ACLU convinced federal courts in 2018 to halt asylum restrictions implemented under President Trump that relied on the same legal authority.

“We were left with no choice but to file this lawsuit,” Lee Gelernt, the lead ACLU attorney behind the lawsuit, told CBS News. “The ban will place countless people at risk and is legally identical to the Trump ban we successfully blocked.”

The complaint filed against the Biden administration argues that the new restriction violates the 1980 Refugee Act, which enshrined into law the commitment to take in noncitizens who were fleeing a “well-founded fear of persecution” in their home countries.

A balancing act?

Biden’s balancing act reflects the importance of immigration for the presidential elections in November. Migrant encounters at the southern border hit a record high at the end of 2023, making immigration America’s top concern in February, according to a Gallup poll.

“The Statue of Liberty is not some relic of American history. It still stands for who we are,” Biden said during a White House speech Tuesday. “But I also refuse to believe that for us to continue to be America that embraces immigration, we have to give up securing our border. They’re false choices.”

This balance has always been a hard one to strike.

The Emma Lazarus poem

The United States is famously a nation of immigrants, founded by liberty-seeking nomads fleeing religious persecution in Europe. For a long time, the crown jewel of the New World operated on a come-one, come-all basis.

This spirit was symbolized by a 225-ton copper présent from France to celebrate the centennial of American independence. Situated on New York Harbor, the Statue of Liberty welcomed millions of immigrants to the “golden door” of America. At its feet lies a poem – “The New Colossus” – that voices the ethos of Lady Liberty. “Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,” she sang to the horizon.

That tune changed significantly in the 1920s, at a time when growing numbers of Americans were expressing nativist sentiment. The percentage of U.S. citizens born abroad rose to 14.7% in 1910, the highest it had been since the first U.S. census was taken in 1790. Immigrants weren’t melting quickly enough in the eyes of the pot.

In response, Congress passed the Emergency Quota Act of 1921, placing a numerical limit on immigration for the first time in American history. Refined in 1924 with the implementation of visas, the quota system was effective at limiting immigration, at least from outside North America.

But the quotas resulted in the turn-away of the Ship of the D____d

These immigration laws were popular among Americans, reflecting the contemporary popularity of eugenics and xenophobia. A San Francisco Democrat and former state senator Edwin E. Grant summed up these opinions in a 1925 essay in The American Journal of Sociology. “[T]he prosperity made possible by our forefathers has lured the parasites of Europe – the scum that could have so well been eliminated from the melting-pot.”

It was the quota system that stopped hundreds of thousands of Jews and other Europeans fleeing Nazi persecution from finding haven in America. At the time, this stance reflected prevailing American public opinion. In a 1938 Gallup poll taken two weeks after Kristallnacht, 72% of Americans said the U.S. should not allow “a larger number of Jewish exiles from Germany to come to the U.S.” The most disgraceful manifestation of these attitudes came in 1939, when U.S. authorities – despite several entreaties to President Franklin D. Roosevelt – turned away an ocean liner with more than 900 Jewish refugees from the port of Miami. After being refused entry by Cuba, the U.S., and Canada, the ship sailed back to Europe and 254 of its passengers perished in the Holocaust.

Such callous hypocrisy in the West, based on anti-immigrant, antisemitic sentiments, caused Adolf Hitler to gloat in 1939: “It is a shameful example to observe today how the entire democratic world dissolves in tears of pity but then, in spite of its obvious duty to help, closes its heart to the poor, tortured Jewish people.”

World War II makes immigration popular again – at least in one context

But the horror of World War II changed the world, and immigration was no exception. In 1948, the newly formed United Nations recognized the right of refugees to seek and enjoy asylum in the face of persecution. Three years later, the UN defined a refugee as anyone who cannot return home “owing to well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion.”

The UN definition of a refugee and its inclusion of “membership of a particular social group or political opinion” offers potential coverage to many kinds of people. Alejandra Oliva, author of the “Rivermouth: A Chronicle of Language, Faith and Migration,” expands on this idea:

“This can mean gay people in a country where gay people face the death penalty just for loving who they love,” she wrote. “This can mean student protestors in a country where there’s been a massive crackdown. Then you start asking questions. Should it cover people who don’t want to belong to gangs? Is that a political opinion? Should it cover women who are survivors of domestic violence? Is that a particular social group?

“There is space for that law to cover whoever we want it to, or to kind of make space for people who fall into the categories that we didn’t foresee in the mid-century when the world looked very different than it does today,” Oliva added.

Immigration reforms in 1965, 1967, and 1980

The U.S. signed onto the UN’s refugee protocol in 1967, two years after officially ending the national origins quota system that had been the basis of American immigration law since the 1920s. This 1965 Immigration Act replaced the national origins system with a new, tiered plan that prioritized family unification and the immigration of skilled workers.

In 1980, Congress passed the Refugee Act, which aligned American policy with international ideals by changing the definition of ‘refugee’ to a person with a “well-founded fear of persecution.” The law also raised the annual ceiling for refugees from 17,400 to 50,000 and required annual consultation between Congress and the president on refugee admissions.

Six years later, Reagan signed the Immigration Reform and Control Act, which was significant for legalizing the status of most illegal immigrants who had arrived in the country prior to Jan. 1, 1984. Most of them were from Mexico, but this group also included thousands of refugees from war-torn Central American countries like Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, and El Salvador.

A decade before the 1980 Refugee Act was passed, only 4.8% of those living in the U.S. were foreign-born. In 2022, 13.9% of the U.S. population were immigrants, a percentage just short of the 1910 spike that preceded much anti-immigrant sentiment. While liberalized American immigration policy is chiefly responsible for this increase, asylum-seekers make up an increasingly large portion of the immigrant influx, as rising instances of conflict and human rights abuses are forcing people to flee their home countries.

The natives are getting restless

Approximately 800,000 people applied for asylum in 2023, a 63% jump from the number of applications filed in 2022. This wave only added to the backlog of asylum cases in the United States: Over two million people are currently waiting for an answer from the federal government about whether they will be granted asylum.

As happened a century earlier, growing numbers of asylum-seekers have generated increasing anti-immigration sentiment. In 2018, while giving remarks on border security, President Trump called “meritless asylum claims” the “biggest loophole” fueling “illegal aliens.”

“An alien simply crosses the border illegally, finds a Border Patrol agent, and using well-coached language — by lawyers and others that stand there trying to get fees or whatever they can get — they’re given a phrase to read,” Trump said. “They never heard of the phrase before. They don’t believe in the phrase. But they’re given a little legal statement to read, and they read it. And now, all of a sudden, they’re supposed to qualify. But that’s not the reason they’re here.”

Some immigration activists disagree with this characterization of asylum-seekers. “In the last few years, asylum has been sort of vilified as like a loophole or a cheat route, or kind of underhanded or sneaky in some kind of way,” said Oliva. “But it’s absolutely not. It’s a human right.”

Ah – ahem, AHEM!

It may be a human right according to the United Nations – and at least implied by existing U.S. law – but it is not a high priority for a majority of U.S. citizens. A 2022 Pew Research poll showed that only 28% of Americans think that “taking in civilian refugees from countries where people are trying to escape violence and war” should be a “very important” goal for the nation’s immigration policy.

It is a never-ending battle. There are those who point to that statue in New York Harbor, to the “Mother of Exiles,” from whose “beacon-hand hand glows world-wide welcome.” They are the dreamers.

“The question is, do we want to give people a safe place to land?” asked Oliva. “Do we want to live up to our reputation and this idea that we have of ourselves as a safe haven nation?”

And then there are the realists, who point to a staggeringly underequipped immigration system, and the very real negative effects unchecked immigration can have on a society.

“I do think there’s a limit to the number of people who we can accept into our nation on an asylum claim,” said Rep. Angie Craig (D-Minn.), a lead voice calling for executive action at the border. “At the end of the day, we cannot have a border where an unlimited amount of people can simply cross.”

This article was originally published by RealClearPolitics and made available via RealClearWire.

Adeline Von Drehle is a rising senior at the University of Missouri studying American history. She will spend the coming year as an Oxford fellow at Corpus Christi College.

-

Civilization3 days ago

Civilization3 days agoVirginia redistricting – the forgotten theater

-

Education5 days ago

Education5 days agoWaste of the Day: DEI Contractors Remain in Military’s K-12 Schools

-

Civilization3 days ago

Civilization3 days agoWhat the Political Attacks on Fetterman Reveal

-

Civilization4 days ago

Civilization4 days agoTrump’s SOTU Speech a Win, But It’s Not Enough

-

Civilization5 days ago

Civilization5 days agoAt a Time of International Turmoil, ARC-ES Can Bring Energy Stability to the U.S.

-

Clergy3 days ago

Clergy3 days agoDecapitating Amalek: Iran, Purim, and the Obligation to Act in Time

-

Executive2 days ago

Executive2 days agoWaste of the Day: Rhode Island Overtime Payments Approach $300,000

-

Civilization4 days ago

Civilization4 days agoTop Library Advocate: Backing Drag Queen Story Hour Supports Parental Choice