Executive

The Current Western-Directed Intervention in Haiti Needs More Legitimacy

Haiti will only suffer from the current Western-directed intervention, with services contracted out to highly dubious players.

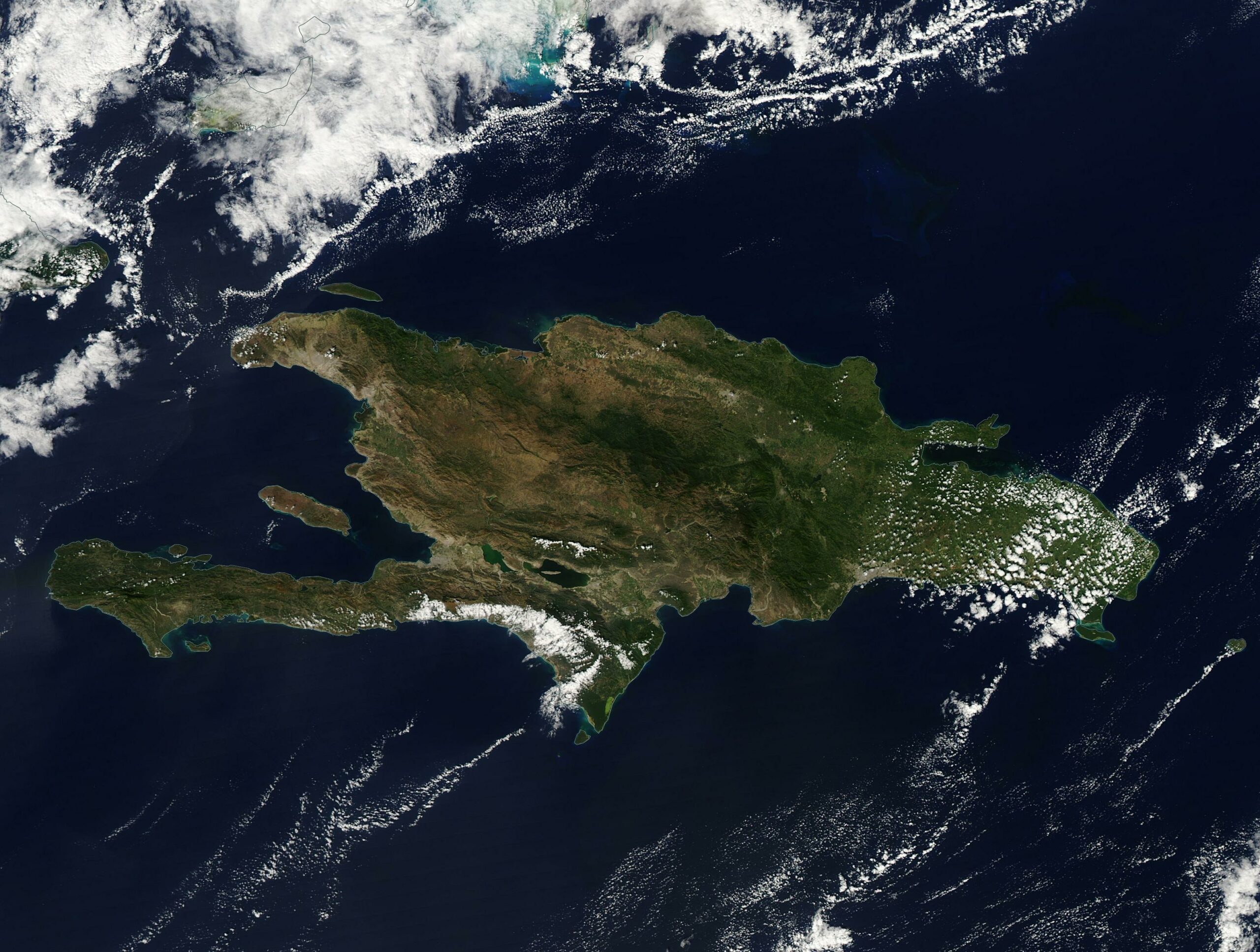

Not surprisingly, Haiti is at yet another inflection point as 2,500 Kenyan police begin to arrive in July of 2024, to deal with 12,000 armed individuals, 600,000 internally displaced persons, and five million suffering from food insecurity, in a national population of 12 million. Authorized by the October 2023 United Nations resolution to deploy a Kenyan-led “stabilization” operation to impose order, the lack of grassroots consultation risks a repeat failure. While these foreign intrusions are nominally guided by sincere goals of democratization, development and stability, the absence of grassroots consultation means they lack the necessary political legitimacy to achieve the goal of winning public Haitian support necessary to create lasting democratic institutions. Haiti has a long history of foreign, particularly U.S., intervention, which either supported dictators in the context of the Cold War, or pursued fundamentally flawed development policy after.

Haiti – recent history

Haiti needs to prioritize the implementation of an indigenous process to democratically select a head of state and government, which is importantly not susceptible to opaque foreign influence. Crucially, the most important issue is the questionable lawfulness of the current Haitian government and its right to agree to the foreign mission. The Haitian presidency has been vacant since July 7 2021, when Jovenel Moïse was assassinated by a group of 28 foreign mercenaries (their mission: kill the president and retrieve a list detailing corrupt Haitian elite who were involved in the narcotics trade). Ariel Henry had been appointed Prime Minster by Moïse, but his term of office was to begin after Moïse was assassinated.

On July 20, Henry was installed as prime minister, but only after an opaque Western ‘Core Group’ (consisting mainly of aid officials in foreign ministries and interest groups representing foreign NGOs operating in Haiti) interceded and demanded that the incumbent Prime Minister, Claude Joseph, stand down in favor of Henry. Ariel Henry’s ascent to power was troubling, not so much by the fact that he had never been sworn in by Moïse and because Haiti’s parliament had not been functioning as elections had not been held as required, but more so because disturbing allegations quickly emerged over links between Henry and at least one of the main suspects in the assassination. Henry’s answer to the assertions was the firing of Haiti’s chief public prosecutor, an act which went without response from the international community.

Trying for a new constitution

As Prime Minister, Henry also enjoyed the de facto powers of the president of Haiti and remained as Haiti’s head of state for almost 3 years (July 20, 2021, through to April 24, 2024). Indeed, early in his tenure, Henry attempted to pass legislation instituting a new constitution, the key amendments being increased powers for the president, the abolition of the position of prime minster in favor of a vice presidency, and the abolition of the Haitian senate. He also failed to hold elections throughout the entire period of his rule, claiming that Haitian turmoil countrywide precluded free and fair elections.

Henry’s legitimacy was questioned by Haiti’s domestic political opposition, and similar issues were raised by a number of key Western nations including the U.S. under President Joseph Biden. Nonetheless, that lack of legitimacy as Haiti’s head of state did not deter the international community – led by the U.S. – from pressuring Henry to agree to the foreign stabilization mission. Ironically, Henry’s power came to an end as he sat down with Kenyan and American officials in Nairobi, Kenya. Henry’s trip sought to finalize the details for the Kenyan-led force’s deployment, including signing the controversial Status of Forces Agreement or SOFA.

Lack of accountability in Haiti

Once out of the country however, armed groups launched a series of coordinated attacks which made it clear he would not be well received if he returned to Haiti. Henry resigned on 24 April 2024, just shy of three years in power. The remnants of the Haitian government, with the support of CARICOM (Caribbean Community) established the Transitional Presidential Council, which helped secure the handing of power over to the interim prime minister Garry Conille. However, the nine-member Council was not deliberative: it was simply presented with the requirement of accepting the deployment of the multinational security mission.

This is a partial symptom of the lack of consultation and accountability, which is a second recurring historical factor responsible for chronic poor results from foreign interventions in Haiti. Western states generally implement their Haitian policies through intercourse with the elite, persistently neglecting grassroots consultations, such as the established community coalition organized in the Montana Accord. The problem is that the elite are essentially anti-democratic.

The police system and judiciary are regularly politicized by Haitian politicians and business leaders, often to affect arbitrary arrests and the detention of political foes. An especially egregious measure was the 2021 passage by then-President Jovenel Moïse of legislation which “classified certain crimes as terrorism, including robbery, arson and blocking public roads, common events during protests.” Thus, political opposition became a criminal activity.

The overthrow of the Duvaliers

The genealogy of the prevailing community groups have their origins in Haiti’s pro-democracy movement that successfully overthrew the Duvalier dictatorship in 1986, of which the most important organization was Lavalas. Haitians are profoundly suspicious of foreign motives because populist Lavalas, in the context of Cold War concerns in Washington, was targeted by right-wing groups as well as by Haitian state institutions like the infamous Service d’Intelligence National (National Intelligence Service, or SIN), founded and funded by the CIA.

The U.S. DIA-founded Front pour l’Avancement et le Progrès Haitien (Front for the Advancement and Progress of Haiti, or FRAPH), was the basis for death squads that murdered thousands of Lavalas leaders and key supporters, as far after the Cold war as 1994. They were implicated in the 1991 coup against President Jean-Betrand Aristide and his Liberation Theology Ti Legliz (Little Church) community organizers, and these ex-regime elements continued to harry Aristide when he was re-installed. The legacy of sidelining populist community organizations in Haiti instead of reliance on elites in Port-au-Prince has become an entrenched practice.

No coordination with groups in Haiti

The current Kenyan-led “stabilization” mission has been devoid of any consultations with key Haitian citizen groups. Indeed, throughout the planning for the current mission, foreign discussions were limited to Prime Minister Henry and his supporters and proceeded from a UN process. Henry was influenced by major foreign powers to make a request for international assistance in October 2022 to deal with the main issue of “criminal actions of armed gangs.” For the Kenyan police to succeed, however, requires a more subtle view of the violence and its solution as essentially political, rather than merely suppressing lawless gangsterism. One such armed group is the emerging Bwa Kale movement, for example, which is the latest iteration of a long-held Haitian tradition of turning to vigilantism in light of the state’s failure to provide internal security.

The most egregious recent example of a misuse of force by the international community was the 2005 United Nations combat assault on an impoverished Port-au-Prince neighborhood with the aim of capturing or killing a single leader of an armed gang. The result of that seven-hour one-sided battle was over 22,000 rounds of small arms, mortar fire and helicopter gunships shooting up the neighborhood and killing dozens of innocent Haitian citizens, including women and children. This lack of consultation extends also to the lucrative business of NGO consultancies.

Services contracted out

What is also problematic (and unique in many ways) about foreign assistance to Haiti is that it takes the form of ‘services’ being contracted out to another state, in this case Kenya, specifically with the appearance of avoiding accountability. Thus, although not a UN mission per se, all UN missions begin with the negotiation of the SOFA and this operation was no different. This crucial legality, the Status of Forces Agreement is the chief legal mechanism that denies the country hosting the UN mission almost all recourse for illegal activities by troops from UN contributing nations, including for acts of murder and rape.

Instead, troop contributing nations are expected to extract their misbehaving troops from the host country and return them to their own nation, to face trial and justice in their own court systems. However, almost no UN troops accused of illegal acts while deployed with the UN have ever faced trial in their home nations. Even without the overwhelming logistics involved in providing a fair trial in another country, most countries prefer to avoid embarrassment and instead sweep the crimes and offenders under the proverbial rug. Thus, UN involvement in the introduction and spread of cholera in Haiti, resulting in the deaths of tens of thousands of Haitians, has seen no one held accountable. Only a small handful of the many UN troops and officials involved in sex trafficking in Haiti, for example, have ever been brought to some kind of justice.

Repeating old mistakes

Without grass-roots consultations, the current UN mission will repeat many of their previous errors. Gang violence is symptomatic of state failure, and while there are certainly some criminal elements engaged in racketeering, a significant number of the armed population are vigilantes and community protection forces, that need societal reintegration. Failure to appreciate this will result in widespread violence inflicted on Haitians who are victims of circumstance. Not approaching community groups in the reform of governance institutions will further entrench corrupt and anti-democratic oligopolistic elites. Permitting populism is vital because it redirects the mobilization of Haitian citizens into the electoral process. A method of aggregating community consulting is also needed to supplant the powerful and chronic influence of NGOs.

This article was originally published by RealClearDefense and made available via RealClearWire.

-

Civilization3 days ago

Civilization3 days agoVirginia redistricting – the forgotten theater

-

Education5 days ago

Education5 days agoWaste of the Day: DEI Contractors Remain in Military’s K-12 Schools

-

Civilization3 days ago

Civilization3 days agoWhat the Political Attacks on Fetterman Reveal

-

Civilization5 days ago

Civilization5 days agoAt a Time of International Turmoil, ARC-ES Can Bring Energy Stability to the U.S.

-

Civilization4 days ago

Civilization4 days agoTrump’s SOTU Speech a Win, But It’s Not Enough

-

Clergy3 days ago

Clergy3 days agoDecapitating Amalek: Iran, Purim, and the Obligation to Act in Time

-

Civilization4 days ago

Civilization4 days agoTop Library Advocate: Backing Drag Queen Story Hour Supports Parental Choice

-

Executive1 day ago

Executive1 day agoWaste of the Day: Rhode Island Overtime Payments Approach $300,000