Constitution

The health care reform bill, standing, and willful confusion

The health care reform bill debate has turned to willful confusion on whether and how that bill harms anyone subject to it. The case of Purpura v. Sebelius has provoked the bill’s proponents to try to say that the case law is not what it really is. Anyone who looks closely at that case law will see that the plaintiffs in Purpura are correct and the government wrong—or lying.

Claims against the health care reform bill

To review, Nicholas E. Purpura and Donald R. Laster Jr say that the health care reform bill violates the US Constitution in fifteen ways:

- The health care reform bill, which raises revenue, started in the Senate, not the House.

- It exceeds Congress’ authority “to regulate commerce among the several States.”

- It raises and supports an army—the Health Care Ready Reserve Corps—with a four-year appropriation.

- It lays a capitation tax without apportionment among the States.

- It taxes the exports of some States more than others. (Taxes on medical devices fall more heavily on the States where their makers build them.)

- Obama had no authority to sign the health care reform bill, or indeed any other bill, into law. He is not a natural-born citizen of the United States.

- It double-taxes some income, and taxes other income that, strictly speaking, doesn’t exist.

- It allows Inspectors General to search or seize private medical records without a warrant.

- Its “individual mandate” deprives people of property without due process of law, and makes involuntary servants of them (by making them buy a service whether they want it or not).

- It directs the States to do the same, in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment.

- It favors some religions and disfavors others, by exempting those who adhere to favored religions from the individual mandate.

- It limits judicial review of several provisions of the bill.

- It taxes some goods and services that members of some, but not all, races use, thus discriminating among races.

- It implicates Congress in a violation of their oath “to bear true faith and allegiance to” the Constitution.

- It abrogates the reserved powers of the States and the People.

Purpura and Laster claim injury in fact on these grounds:

- The individual mandate forces them to buy something, or pay a fine (or a tax) for not buying it, whether they want to buy it or not.

- The medical-device taxes, and taxes on tanning equipment and so on, are extra expenses that, absent the bill, they would not have. (In fact, several tanning salons have recently closed their doors rather than pay this tax.)

No court, hearing a case on appeal, can consider any argument that appellants (or petitioners) or appellees (or respondents) did not raise at or prior to trial. Hence raising fifteen different counts, even though most of them refer to the same act. Any plaintiff alleges all the ways that a defendant broke the law, even by one act.

The issue before the Third Circuit

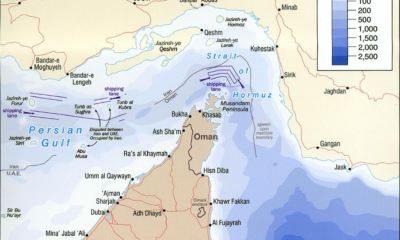

The James A. Byrne Federal Courthouse, Philadelphia, PA, home of the Third Circuit Court of Appeals. More than one health care reform bill case is on appeal here. Photo: US Department of Justice

Purpura and Laster brought their case to the Third Circuit Court of Appeals after the District Court said that they lacked standing. In short, the court held that the law does not harm them. But the court did not reason that “they suffered no worse harm than would anybody else.” The court held that the law does not harm them at all. Specifically, the individual mandate should not worry them because, for all they do or can know, they would have employer-based coverage by 2014.

The court could not so reason today, if indeed it had any justice to its reasoning before. Since then, several studies have predicted that half of all employers in this country will drop coverage for their employees. The health care reform bill makes private insurance too expensive. That study alone would show the strongly probable harm that would come to any citizen or lawful resident.

Stand on liberty

But Purpura and Laster stand on a more fundamental principle. The health care reform bill harms anyone concerned for his liberty. A measure that fines someone for not buying a good or service, takes his liberty from him. A measure that lays a capitation tax on him likewise takes his liberty from him. And a measure that interferes with a power reserved to the States, also threatens the liberties of every lawful resident of that State.

The landmark case of Bond v. United States makes that abundantly clear. Mrs. Bond, a classic “woman scorned,” put a caustic substance on another woman’s front doorknob, car door handle, and mailbox. The substance burned the other woman’s hands. She called police. They arrested Mrs. Bond.

Now the State of Pennsylvania could have charged her with something routine, like assault with a deadly weapon or criminal trespass. Instead, the federal government charged her with possession of a noxious chemical with intent to harm a human being, in violation of—get this—a law that Congress passed to carry out a United Nations convention. In short, the federal government treated her as if she were handling nerve gas.

In the Federal District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania, Mrs. Bond’s lawyers moved to dismiss the charge because the federal law infringed on Pennsylvania’s police powers, in violation of the Tenth Amendment. The court denied the motion. So Mrs. Bond pleaded guilty—conditionally. She reserved the right to challenge the chemical-weapons conviction in a higher court.

The Third Circuit Court of Appeals denied her appeal because she lacked standing. The court held that the Tenth Amendment protects States but not their citizens or lawful residents. Thus only the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania could bring a Tenth Amendment action.

The Supreme Court, on June 16, 2011, disagreed.

Federalism has more than one dynamic. In allocating powers between the States and National Government, federalism “ ‘secures to citizens the liberties that derive from the diffusion of sovereign power,’ ” New York v. United States, 505 U. S. 144, 181. It enables States to enact positive law in response to the initiative of those who seek a voice in shaping the destiny of their own times, and it protects the liberty of all persons within a State by ensuring that law enacted in excess of delegated governmental power cannot direct or control their actions. See Gregory v. Ashcroft, 501 U. S. 452, 458.

And:

The law to which she is subject, the prosecution she seeks to counter, and the punishment she must face might not have come about had the matter been left for Pennsylvania to decide.

Several commenters have said, in this comment space, that Mrs. Bond gained her standing when the federal government charged her with a crime under an arguably unconstitutional act. Those same commenters admit elsewhere that one does not have to break the law to gain standing to challenge the Constitutionality of that law. One need only be subject to that law.

Some say that standing requires a “particular” injury that most people do not suffer. That argument defies logic. If the government decides today to forbid anyone to criticize it, that law would apply to everyone. By that argument, then, no one would have standing. And by the reasoning that the New Jersey District Court used in Purpura, anyone could avoid the injury-in-fact by a simple expedient: keep your mouth shut!

Two alleged countervailing cases

Those same commenters mention two other cases that, they say, countervail Bond. They are:

- Arizona Christian School Tuition Organization v. Winn et al., 09-987 (Decided April 4, 2011.)

- Doremus v. Board of Ed. of Hawthorne, 342 US 429 – Supreme Court 1952

Plaintiff Winn sued the Arizona Christian School group because they got a tax credit that Mr. Winn said violated “separation of church and state.” Doremus sued the Hawthorne (New Jersey) Board of Education because his children had to endure hearing the reading of Bible verses in class.

In each case, the Supreme Court held that the plaintiffs did not have standing. In Arizona, the court said that a tax credit did not harm any particular taxpayer, and Winn could not show that the tax credit put his community in financial straits. Doremus did not show that the school was interfering with his right to practice his religion outside the classroom, or forcing his children to convert to, or from, Christianity or Judaism. (For the record, the verses came from the Old Testament, not the New.)

That anyone would still use Doremus as a case to say that ordinary citizens lack standing makes no sense today. Atheists routinely file such lawsuits today, and prevail, strictly on the “offensiveness” test. If they have standing, why wouldn’t Purpura and Laster against the health care reform bill?

But the commenters make another mistake. A decision to forgive one person’s taxes is a political decision. But to tax, or fine, one particular person for doing a thing, is to deprive that person of the liberty to do that thing. (To make that thing a felony or misdemeanor is a political act, subject to Constitutional limits.) And to tax, or fine, that person for not doing a thing, is to enslave him and force him to do that thing. Those are definite, particular harms. And in our courts, the person suffering that harm has the right to seek redress in the courts.

Cases relevant to the health care reform bill

These commenters ignore the case of Thomas More Law Center v. Obama, Court of Appeals, 6th Circuit 2011. The Thomas More Law Center sued the government (naming Obama as the defendant) over the health care reform bill, and especially over the individual mandate. True enough, the Sixth Circuit found in favor of the government. (The Thomas More Law Center is asking for Supreme Court review.) But before the Sixth Circuit got to that point, it asked itself whether the plaintiffs had standing. The court’s answer: yes. The Thomas More Law Center showed actual injury and imminent injury. Either form of injury is enough for standing.

If the Thomas More Law Center has standing to challenge the health care reform bill, then Purpura and Laster have even more standing. As ordinary persons, they will have to pay the tax, or fine (or whatever the government wishes to call it.)

Even more telling is Florida ex rel. McCollum et al. v. HHS et al., the case that Judge Roger Vinson decided in the District Court for the Northern District of Florida. Judge Vinson, as everyone knows, found for the plaintiffs. (That case is before the Eleventh Circuit.) And he could not even have done that much before ruling on standing. Most people forget this key detail: the 26 States in that lawsuit were not the only plaintiffs. The National Federation of Independent Businesses, and two private persons, also joined as plaintiffs.

Judge Vinson said that the two private persons had standing to complain against the individual mandate in the health care reform bill. Purpura began with two persons; over 100 others have since joined. Judge Vinson has set a clear precedent that private persons have standing to challenge the health care reform bill in court. States are not the only parties with such standing.

(Another thing that people forget about the Tenth Amendment: it reserves certain powers to the people, not to States alone. So a person, being “one of the people,” has standing to challenge any federal law that infringes on any of his “reserved powers.”)

Conclusion

By any reasonable standard whatsoever, the New Jersey District Court used specious reasoning to rule that Purpura and Laster lack standing to challenge the health care reform bill. If the Third Circuit decides to accept that reasoning, Purpura and Laster will go to the Supreme Court. The Bond precedent says that they will prevail—particularly because the Court decided the Bond case after it decided the Arizona case.

The Motion to Dismiss

Some have said that the Motion to Dismiss “stopped the clock” on the deadline for answers to the counts that Purpura and Laster alleged against the health care reform bill. But: the government filed that Motion in February of 2011, well after the deadline had passed. Purpura and Laster filed their suit against the health care reform bill in September of 2010. The Federal Rules of Civil Procedure give the United States sixty days to respond to a complaint naming it as defendant. Those sixty days ran out in November, and the DOJ never filed anything but a response to an injunction request during that time. The government did ask for an extension of time, but only after Purpura and Laster moved for default judgment on December 9, 2010—again, well after the response deadline.

Furthermore, “lack of subject matter jurisdiction” (in this case, no standing) is the only special defense that the government has raised. A defendant may raise that defense at any time. But if a defendant has a defense like inadequate service of process, they must raise that within the deadline, or they waive it. (The only way that that could apply: Purpura and Laster, when they served their complaint in September of 2010, forgot to serve a copy on the US Attorney for New Jersey. But his office since asked Purpura and Laster to send them a copy, which they did. Therefore, they have waived that defense.)

All this means that, once any court rules that Purpura and Laster have standing, they win by default. The consequences are much further-reaching than a judgment against the health care reform bill. They include a judgment against the man now holding office as President of the United States.

This might be why a commenter asked,

[Y]ou don’t really believe that a court will oust a president, nullify an election, install an un-elected private citizen and destroy the government based on a default, right? Even without knowing that it’s insanely easy to get a default judgment overturned, you couldn’t possibly think that the court would do all that because of one missed deadline, right?

As a matter of fact, Richard Cheney, the last elected Vice-President, would become President until another election settles the dispute. So he would not be “an un-elected private citizen.”

More broadly, the tone of the above question shows how breathtaking the consequences will be. This will be a magnitude-9.0 or stronger political earthquake. Then again, so was the case of United States v. The New York Times and The Washington Post. Or United States v. Nixon.

Featured image: the Constitution of the United States. Photo: National Archives.

Related:

- Frustration

- More motions

- Recusal motion

- Default motion

- Appeal skirmish

- Commerce, health care, and distortion

- Plaintiffs seek injunction

- Appeal delayed

- Plaintiffs have standing after all

- DOJ wants more time on HCR appeal

- Another appeal

- Hazardous to your health

- Court dismissal

[amazon_carousel widget_type=”ASINList” width=”500″ height=”250″ title=”” market_place=”US” shuffle_products=”True” show_border=”False” asin=”B00375LOEG, 0451947673, 0800733940, 0062073303, 1595230734, 1936218003, 0981559662, 1935071874, 1932172378″ /]

Terry A. Hurlbut has been a student of politics, philosophy, and science for more than 35 years. He is a graduate of Yale College and has served as a physician-level laboratory administrator in a 250-bed community hospital. He also is a serious student of the Bible, is conversant in its two primary original languages, and has followed the creation-science movement closely since 1993.

-

Civilization3 days ago

Civilization3 days agoVirginia redistricting – the forgotten theater

-

Civilization4 days ago

Civilization4 days agoWhat the Political Attacks on Fetterman Reveal

-

Civilization5 days ago

Civilization5 days agoTrump’s SOTU Speech a Win, But It’s Not Enough

-

Civilization5 days ago

Civilization5 days agoAt a Time of International Turmoil, ARC-ES Can Bring Energy Stability to the U.S.

-

Clergy4 days ago

Clergy4 days agoDecapitating Amalek: Iran, Purim, and the Obligation to Act in Time

-

Executive2 days ago

Executive2 days agoWaste of the Day: Rhode Island Overtime Payments Approach $300,000

-

Civilization5 days ago

Civilization5 days agoTop Library Advocate: Backing Drag Queen Story Hour Supports Parental Choice

-

Executive1 day ago

Executive1 day agoWaste of the Day: Prediction: Debt Will Soon Break Record

On the contrary, I understand them very well.

Say, don’t I know you from somewhere…?

“Critic”? You? No. You don’t rate that much. A true critic (from the ancient Greek word for a judge) uses critical, that is, judge-like, thinking.

You’re not thinking like a judge. At best, you’re thinking like an advocate.

What you’re really doing is acting like a political operative. You have the script down pat from Saul Alinsky’s Rules for Radicals.

Say what you will; you just made an excuse. You can’t answer my arguments. You won’t admit that all that some of those so-called judges have, is their own prejudice on this case, and the continuing belief that they can make those two gadflies go away. They won’t, and I won’t.

What you do, is your own business. But now you know why I leave this comment space open. So that guys like you can blow the gaffe and illustrate, better than I can, what you Saul Alinsky students are really like.

From page 13 of Bond v. United States:

“An individual who challenges federal action on [Tenth Amendment] grounds is, of course, subject to the Article III requirements, as well as prudential rules, applicable to all litigants and claims. Individuals have ‘no standing to complain simply that their Government is violating the law.’ Allen v. Wright, 468 U. S. 737, 755 (1984). It is not enough that a litigant ‘suffers in some indefinite way in common with people generally.’ Frothingham v. Mellon, 262 U. S. 447, 488 (1923) (decided with Massachusetts v. Mellon). If, in connection with the claim being asserted, a litigant who commences suit fails to show actual or imminent harm that is concrete and particular, fairly traceable to the conduct complained of, and likely to be redressed by a favorable decision, the Federal Judiciary cannot hear the claim. Lujan, 504 U. S. at 560–561. These requirements must be satisfied before an individual may assert a constitutional claim; and in some instances, the result may be that a State is the only entity capable of demonstrating the requisite injury.”

This language is nothing if not an attempt to keep people from misinterpreting Bond in precisely the way that Purpura and Laster have. Their claims boil down to “the Government’s passage and implementation of the ACA is illegal under various constitutional provisions, all Americans are injured when the constitution is violated, we are Americans who have thus been injured, so we have standing.” In short, they are claiming that they “suffer in some indefinite way in common with the people generally.” That much is clear from their repeated insistence on framing their claims as grievances of “We The People.” But a purely philosophical / academic sense of outrage or disagreement over perceived constitutional violations isn’t enough to get a party over the standing hurdle, regardless of how justified the outrage or disagreement is, because it doesn’t constitute a tangible, concrete injury.

Similarly, you talk about “loss of liberty” and, in the most philosophical, Isaiah Berlin-esque sense of that word, you are correct to state that any law that prohibits an act restricts a person’s “liberty.” But to the extent such a restriction can be said to constitute an injury, it is an injury of a type that’s far too abstract and ethereal to grant standing.

The Sixth Circuit’s holding in the Thomas More Law Center case is of no help to Purpura and Laster. In that case, the Court held that the plaintiffs established both actual injury and probability of imminent future injury because they submitted affidavits in which they essentially said “we don’t have health insurance, and the impending requirement that we purchase health insurance in order to avoid breaching the minimum coverage provision of the ACA has forced us to modify our spending and saving habits.” And there you have it: that forced modification of spending and saving habits represents a concrete, individualized injury.

In State of Florida v. U.S. Dep’t of Health and Human Servs. you see very similar affidavits from the private, individual plaintiffs and again, a finding that they had standing on the basis of the facts stated in those affidavits. But Purpura and Laster offer no such information about themselves. We know they think the ACA is an unconstitutional restriction on their general liberty, but they provide no information about how it will affect them on an individual basis.

Your example: “If the government decides today to forbid anyone to criticize it, that law would apply to everyone. By that argument, then, no one would have standing” misconstrues the “particularity” requirement. Nobody is claiming that an individual can never have standing to challenge a law if the law applies to everyone. But the individual has to bring something more to the table than “This law applies to me and violates the first amendment, and I have a direct interest in seeing the first amendment upheld.” So, for your example, the individuals who would have standing are those who are arrested, charged, and/or punished under the law (and those for whom those things are imminent) or those who can show that they altered their behavior in some way to avoid breaching the law.

Lujan v. Defenders of Wildlife has a great discussion of this principle (there’s a reason the Bond decision cites to it): “We have consistently held that a plaintiff raising only a generally available grievance about government — claiming only harm to his and every citizen’s interest in proper application of the Constitution and laws, and seeking relief that no more directly and tangibly benefits him than it does the public at large — does not state an Article III case or controversy.”

On to (even) duller matters. Purpura and Laster filed their complaint in district court on September 20, 2010, but did not properly serve the United States attorney until December 15, 2010. Rule 12(a)(2) calls upon the government to answer via a responsive pleading or 12(b) motion within “60 days after service on the United States attorney.” So the government had 60 days from December 15, 2010, to answer the complaint itself. However, on December 9, 2010, Purpura and Laster filed a motion for summary judgment. The government was initially instructed to respond to that motion by January 3, 2011. The government then invoked an automatic two-week extension of that deadline and the court set a new one, for January 17, 2011. The government filed its opposition to the motion for summary judgment on January 17, 2011, in the form of a 12(b)(1) motion for dismissal that was subsequently granted. Thus, there was no default here because the government never missed a deadline. And no, correctly relying on the rules of proper service to calculate when a response is due does not constitute raising improper service as a defense to a complaint, so the rules for raising improper service as a defense are irrelevant here.

Furthermore, even if the Third Circuit were to conclude that the District Court somehow erred in extending the deadline from January 3, 2011 to January 17, 2011, the outcome absolutely would not be a default judgment in favor of Purpura and Laster. A default judgment serves to penalize the party against whom it is entered. Where the court explicitly states that a filing is due by a specific day, and a party relies on that statement in determining when to submit the filing, the relying party has done nothing wrong, and there is thus no basis for penalizing them well after the fact.

The best possible outcome that Purpura and Laster can hope for from this appeal is a ruling that they do, in fact, have standing to bring their claims. I think it’s a faint hope at best, for the reasons stated above. But should it happen, the case will then be remanded back to the District Court, which will issue instructions for the government to submit a responsive answer that addresses the merits of the claims.

Why is it not just enough to say that our trusted officials

(judges and the like ) are asuming authority never granted

them by our ruling document. Their authority comes directly

from the consent of the citizens, and it is encumbent upon

the citizens to eradicate any abuse of our trust.

The power belongs to the people, not the pathetic, foolish

puppits they dangle in our face, notwithstanding any

decision or precedent courts assume they can force we the

citizens to accept.

Can you believe it?? “Notwithstanding” is the most confusing word I encountered in our Constitution.

Terry, you said that “Some say that standing requires a “particular” injury that most people do not suffer. That argument defies logic. If the government decides today to forbid anyone to criticize it, that law would apply to everyone. By that argument, then, no one would have standing.”

Incorrect. People who are prosecuted for criticizing the government would have standing, a la Bond. That’s the difference.

So what you’re saying, contrary to your friend earlier in the thread, is that you have to run afoul of the law and suffer a criminal prosecution, or have a civil fine levied against you, to have standing. Nothing in the opinions of the cases that the other commenter cited supports any such interpretation.

I have read Article lll of our Constitution numorous times,

searching for this peculiar interpretation of standing the

more erudite than I, lawyers, and judges glean from its

content. To me it seems to say the very opposite they wish

us less educated to believe. I understand it to say that

citizens have standing in any case of law or controversies.

I can only surmise they intentionaly create convoluted

definitions and rules of procedure for the sole purpose

of keeping us confused, under their control, and in awe

of their superior knowledge.

In other words, like the tailors in The Emperor’s New Clothes, they say that their interpretations of Article III are incomprehensible only to those who are stupid or unfit for their posts.

The two plaintiffs in this lawsuit make that precise argument: that Article III gives standing to absolutely any citizen who notices that something that the government has done, violates the Constitution.