Civilization

The Long View

Any civilization must take The Long View to survive. That applies equally to space programs as to the preservation of values.

A new Congress is preparing to convene in earnest, and The Free Press is (perhaps) preparing another Twitter Files release. While we wait, we should reflect on different possible views we can take toward events yet to come. CNAV has noticed, over its nearly twelve years of operation, that too many take a short view. In fact, a society – a civilization – must take the Long View, or it will not survive. But those who do take the Long View, are better able to survive while others do not.

The Long View – an explanation

Before considering The Long View versus the short view, one must define value. The late Robert A. Heinlein articulated the best definition of value. Value is the relationship between:

- What a person can do with a thing – its use to him, and

- What he must do to get it – its cost to him.

The Long View is the view beyond the lifetime of any one person. As such it cannot possibly be of immediate use to anyone now alive. (Or so one might think.) So The Long View creates a problem for anyone holding it. He must pay its costs now – but the uses will come, not to him, or even to his generation, but to the next and following generations.

Greed and spite are two classic short-view motives. The greedy person wants all he can use (or thinks he can use) now. Let others, especially the next generation, pay the costs. The spiteful person has a worse motive: he wants to hurt others, whatever the costs to himself or anyone else. An individual acting from greed or spite causes damage enough – damage being that which imposes costs and destroys usefulness. An entire society that embraces the short view and not the Long, must inevitably destroy itself. As did Rome in the Middle Ages (and the Byzantine Empire a thousand years later). As “The West” threatens to do now. Books must balance, and debts – deferred costs – must be repaid.

Examples

Low birth rates in civilized countries worldwide reflect short-view thinking. To too many people, children are a bother. No one thinks about the next generation, or even about who will take care of them in their old age. Children do impose an immediate cost – and in an industrial society, they are of no immediate use. That anyone would make this kind of calculation, probably shows that our society has forgotten how to love. Nevertheless, people are making that calculation, even if only subconsciously.

And how does anyone rest easy about who will take care of them in old age? Simple: Franklin Delano Roosevelt encouraged people to turn over their old-age cares to the government. The full name of Social Security is the Old Age, Survivorship and Disability Insurance Program. And that’s no accident.

It is also unsustainable. At best it recalls the famous swindle by one Carlo Pietro Giovanni Guglielmo Tebaldo Ponzi. At worst it puts the government itself at moral hazard. The “welfare state” creates the concept useless eater. The only use the clients of “Social Security” or “welfare” have to the government, is continued electoral support of those now in power. Once that use ends, their usefulness ends. Hence the Canadian push to offer suicide facilitation, not palliation, to those suffering from age-related or other chronic infirmities.

Traditional societies take The Long View

Some traditional societies still exist, and offer an instructive contrast. Any traditional society respects its elders, and turns to them for advice. Some might object that this leads to stagnation. Yet these societies persist.

Consider the Amish, who, when they came to America in the eighteenth century, determined to separate from the larger world. They maintain as few connections as possible – no more than a community telephone, and no entertainments. Because they separated from the world, they are independent of it and could easily survive a general social collapse. More to the point, they support family at all levels. True, some wags said they essentially avoided all technological advancement after 1850. (Actually that’s when the Great Schism between the Old Order and the New happened. That had nothing to do with technology.) But they persist. And if our modern technology fails, as often happens after great storms, they can survive without it.

Now had the modern society taken The Long View, it would have permitted, even encouraged, its members to keep systems in place enabling them to survive in the face of technological failure. This did not happen. So when technology fails, people die.

Non-traditional examples

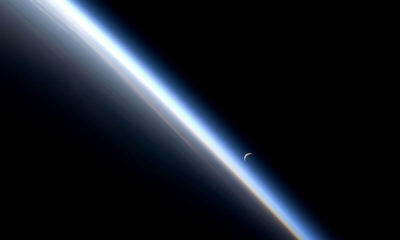

Now consider an application of The Long View beyond a traditional, agricultural society. Elon Musk, founder of SpaceX (and Tesla, and Neuralink, and “The Boring Company”), takes a very Long View. Years ago he explained his Long View to the International Astronautical Federation, in Guadalajara in 2016 and Adelaide, Australia in 2017. Basically he gave humanity a choice:

- Stay on Earth and wait for some future “extinction-level event” to wipe us out, or

- Go out to other planets, and eventually to other stars, so that no one disaster could wipe us out.

He also offered something that could be “useful” to anyone having any sort of hope:

You want to be inspired by things. You want to wake up in the morning and think the future is going to be great. And that’s what what being a spacefaring civilization is all about.

And that’s The Long View – the notion that the costs you pay now, will buy things of greater use later.

To that end he developed rocket ships with reusable boosters and payload carriers. He is now developing the ultimate fully reusable rocket, able to deliver payloads almost as heavy as what the Saturn V could deliver. Happily, at every stage he develops things useful to other people, so those people will pay him for those uses. The revenues finance his next development projects, all leading to the same goal: a multiplanetary future for humankind.

The ultimate Long View

But has Elon Musk even conceived of how long a Long View a multiplanetary future will require? Founding a city on Mars, his first grand design, will present enough of a challenge. But he can fund that with “current profits,” and that city will be even more profitable. It will be the ideal launch point for mining and other expeditions to the asteroids and outer planets.

But Musk is on record talking hopefully of traveling to the stars and “taking life with us.” That will require a “wait” over many generations, if not for his company, then for any “civilizational state” that contracts with it for a program of multiplanetary – indeed, multi-stellar – expansion.

Lay aside Miguel Alcubierre’s speculations on faster-than-light travel. Before him, Robert D. Enzmann developed propulsion plant and ship designs one can build now. These ships might be able to travel at a significant fraction of the speed of light – perhaps only slightly slower. But no faster.

A program to “carry life” to the stars

True, relativity will cut perceived transit time for the officers and crew of any colony or scout ship. (That benefit would apply to a robot scout as well.) But the “launch authority” must wait the full time: transit time of the scout(s) to a target star, then transit time for a legible signal (or worse, the scout itself) to return to Earth. That’s nine years – minimum – to scout the Alpha Centauri double star, or Proxima Centauri (“Alpha Centauri C”). Figure twenty, twenty-five, or thirty years to scout the nearest stars that might have either Jupiters or Earths orbiting it. Projects Mercury, Gemini and Apollo combined lasted for twelve years. Then the Long View failed, resulting in cancellation.

Could this be the true resolution of the Fermi Paradox? The Fermi Paradox states that, though the probability of the existence of an extra-solar civilization is extremely high, no such civilization has contacted us. Where is everybody? Might they have given up, because they didn’t take the Long View?

Any space program, even one limited to our solar system, requires the Long View. But a similar Long View informed the decisions that the major powers made during the Age of Exploration. A multiplanetary expansion program would appeal to a true “civilizational state” hoping to perpetuate its values. The benefits might be entirely non-material: the peace of mind of knowing that the human race, and civilizational values, would endure.

In any other context, The Long View prevails. The short view destroys itself.

Terry A. Hurlbut has been a student of politics, philosophy, and science for more than 35 years. He is a graduate of Yale College and has served as a physician-level laboratory administrator in a 250-bed community hospital. He also is a serious student of the Bible, is conversant in its two primary original languages, and has followed the creation-science movement closely since 1993.

-

Accountability4 days ago

Accountability4 days agoWaste of the Day: Principal Bought Lobster with School Funds

-

Civilization1 day ago

Civilization1 day agoWhy Europe Shouldn’t Be Upset at Trump’s Venezuelan Actions

-

Executive2 days ago

Executive2 days agoHow Relaxed COVID-Era Rules Fueled Minnesota’s Biggest Scam

-

Constitution3 days ago

Constitution3 days agoTrump, Canada, and the Constitutional Problem Beneath the Bridge

-

Christianity Today1 day ago

Christianity Today1 day agoSurprising Revival: Gen Z Men & Highly Educated Lead Return to Religion

-

Civilization2 days ago

Civilization2 days agoThe End of Purple States and Competitive Districts

-

Executive2 days ago

Executive2 days agoWaste of the Day: Can You Hear Me Now?

-

Civilization5 days ago

Civilization5 days agoThe Conundrum of President Donald J. Trump