Entertainment Today

Making Music with His Friends

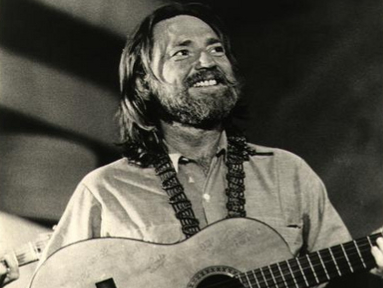

A tribute to country star Willie Nelson (born 1933), who loves nothing so much as making music with his friends.

The following is a condensed version of “Making Music with His Friends” by John G. Grove, published at Law & Liberty.

From childhood, he has admired the straightlaced singing cowboy Gene Autry; he’s also the world’s most famous pot-smoking hippie. In the recently released docuseries Willie Nelson and Family, this might stand as the symbol of a great creative tension in the life of the country music star. Throughout his life, Willie has appreciated traditional country music. But flowing out of his hippie mentality, he also has a compelling drive to do things his own way. That combination was just what country music needed when Willie first emerged.

Willie explains that great music “never goes out fashion,” even if it undergoes surface changes. The country music executives in the 1960s didn’t quite buy that. They were focused on following the fashion, and at that time, the fashion was “The Nashville Sound,” which mimicked popular music with effusive vocals, lush strings and choirs in the background, and comfortable lyrics that appealed to sophisticated middle-class listeners. When Willie moved to Nashville, he found instant success as a songwriter, but stuck in the stultifying “Nashville sound” box, his own albums did not take off.

With his relaxed vocal phrasing, behind-the-beat manner of singing, and the unique sound of his classical guitar, Willie’s style called for less production and less pretension. But the record executives didn’t think anyone wanted to listen to simpler songs in the older folk, western, and honky-tonk styles. It didn’t occur to them that someone could restore that style of music by reinventing it. Willie had always loved old-school country stars like Autry, Jimmie Rodgers, and Ernest Tubb, but he had also been inspired by non-country artists, including Django Reinhardt and Frank Sinatra. Willie wanted to sing in the tradition of that old country music, but he was going to do it his own way.

When Willie left Nashville for Austin in 1972, he found people more willing to experiment. It was a place where “the hippies and the rednecks got along,” thanks in part to shared love of a music that was a blend of rock, folk, and country sounds.

Success came in direct proportion to the amount of control Willie got over his records. Albums from the mid-‘70s like Red Headed Stranger and The Troublemaker demonstrate his imaginative engagement with the tradition he operated in. The series emphasizes Red Headed Stranger’s sparse instrumentation and minimal production. While the presenters are right to describe that approach as trailblazing and innovative, they don’t do much to stress how traditional of an album it is, too. Its simple, “man-with-guitar” sound was a throwback, and Willie has written elsewhere that he had country artists of the ’40s in mind when he recorded it.

The gospel album was a staple of any country recording artist of the ’60s and ’70s. But it was often a phoned-in affair. None of them had the life and freshness of The Troublemaker. As Willie and his sister Bobbie relate in the interviews, the two were singing songs they had sung in their grandparents’ home as children, rendered in a honky-tonk style with an instrumentation that would define his sound. That authentic sound helped an album full of Baptist hymns not only reach the top of the country charts, but also crack the Billboard 200 pop charts.

For a tradition to be more than stale repetition, it needs imagination that can make it new, finding fresh ways to bring out its merits. Willie offered just that sort of imagination, helping to create what would be termed “outlaw country.”

But he would then go on to transcend the country genre. He recorded American songbook staples on Stardust (which again infuriated the record bosses, who now wanted “more of that outlaw shit”) and then covered several pop and rock songs on Always on My Mind. His cross-over success didn’t come from trying to mimic anyone else’s sound. He never ceased to be a country artist; he just showed that a country artist could sing a good song, no matter where it came from.

“The life I love is making music with my friends”: so goes Willie’s 1980 hit “On the Road Again.”

The series also emphasizes the many friends that defined Willie’s life and his music, from his sister Bobbie to Waylon Jennings and Merle Haggard to Ray Charles and Snoop Dogg. As he found success, Willie brought his friends up with him and made deep and profound new friendships in unexpected places.

The waltz through Willie’s life includes many other interesting vignettes on all the things one would expect—his legendary guitar named Trigger, his notorious, smoke-filled tour bus, and his creation of Farm Aid. But the producers wisely chose to focus on stories that all, in some form, revolve around the bigger, unifying theme of his life—making music with his friends.

This article was originally published by Law & Liberty Exclusive and made available via RealClearWire.

John G. Grove is managing editor of Law & Liberty. He previously taught political science at Lincoln Memorial University.

-

Accountability2 days ago

Accountability2 days agoWaste of the Day: Principal Bought Lobster with School Funds

-

Constitution2 days ago

Constitution2 days agoTrump, Canada, and the Constitutional Problem Beneath the Bridge

-

Executive22 hours ago

Executive22 hours agoHow Relaxed COVID-Era Rules Fueled Minnesota’s Biggest Scam

-

Civilization22 hours ago

Civilization22 hours agoThe End of Purple States and Competitive Districts

-

Civilization4 days ago

Civilization4 days agoThe devil is in the details

-

Executive4 days ago

Executive4 days agoTwo New Books Bash Covid Failures

-

Civilization4 days ago

Civilization4 days agoThe Conundrum of President Donald J. Trump

-

Executive4 days ago

Executive4 days agoThe Israeli Lesson Democrats Ignore at Their Peril