Civilization

How Hebrew Almost Became America’s Official Language

Hebrew as America’s official language? That myth actually persists, with two Presidents of Yale College weighing in on opposite sides.

Legend has it that nearly two and a half centuries before President Trump declared English as the official language of the United States, Hebrew was proposed as an alternative.

The Marquis de Chastellux proposes Hebrew as the language of America? Satire, of course

In 1791, the Marquis de Chastellux (François Jean de Beauvoir), an enigmatic Frenchman who served as a general in the American Revolution, published an astonishing claim in his travelogue memoir. Chastellux reported that “some persons were desirous, for the convenience of the public, that the Hebrew should substituted for the English … that it should be taught in the schools, and made use of in all public acts.” Intriguingly, other versions of this myth identified French, German, or even Greek as the proposed language.

While Trump’s executive order seems unprecedented, such stories suggest that debates about national language policy trace back to the founding period itself.

While obviously farcical and far-fetched, the myth of a proposed Judeo-American founding language reveals political tensions of national identity in the nascent United States.

Chastellux’s travelogue offers a helpful window into this historical moment. As he noted, the “national pride” of revolutionary-era Americans “suffered not a little from the reflection … of the language of the country being that of their oppressors.” To elide this reality, some purportedly preferred to call their language “American” instead of English. Within this context, Chastellux humorously included the anecdote about Hebrew, perhaps to poke fun at American anxieties of linguistic independence.

Why Hebrew?

But why, of all languages, did Chastellux select Hebrew for his satire? One answer appeared in a review of Charles Jared Ingersoll’s “Inchiquin the Jesuit’s Letters” (1810), a fictional correspondence of an Irish Catholic expressing a laudatory view of America.

Ingersoll’s “Inchiquin” had proposed that Americans adopt French, the literal lingua franca of the age. In the London-based Quarterly Review, an anonymous reviewer of “Inchiquin” disparagingly remarked that Hebrew, rather than French, had once been recommended as the national language, “considering the Americans, no doubt, as the ‘chosen people’ of the new world.” A few years later, an anonymous New Englander, most likely Yale President Timothy Dwight IV, retorted that he had never before heard of the reviewer’s claim, and he estimated that neither had 99% of Americans.

Nevertheless, the British reviewer alluded to a kernel of truth that may have sparked Chastellux’s imagination: some Revolutionary Americans did view themselves as God’s chosen nation akin to ancient Israel. Moreover, as numerous scholars have shown, the Bible – especially the Old Testament – abounded in the literature of the period.

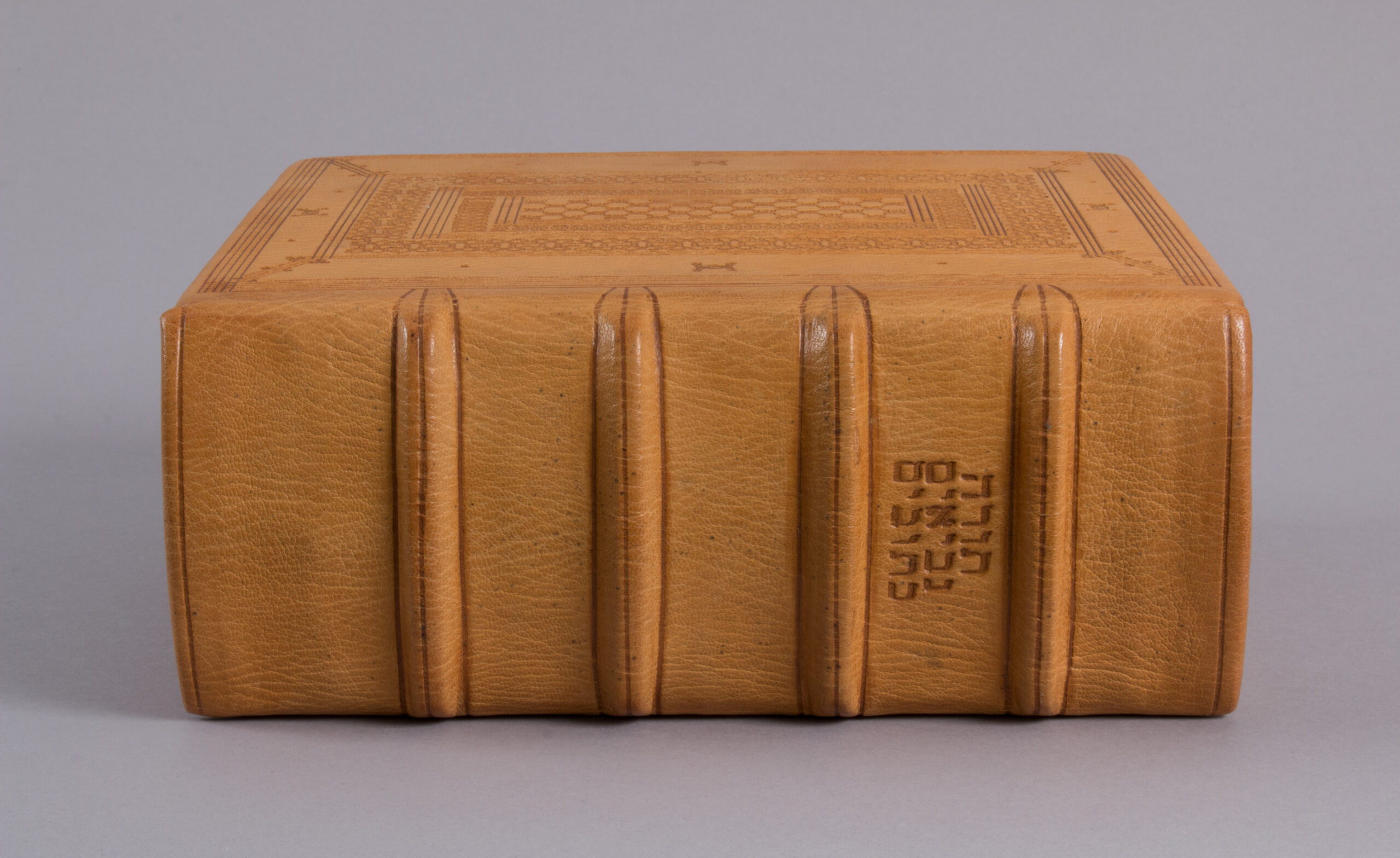

Ezra Stiles, Dwight’s predecessor to the Yale presidency, studied kabbalah (Jewish mysticism) and required Hebrew classes at the university. One Jew even addressed Stiles as the Yale rosh yeshiva! While a far cry from a national language policy, this context helps explain a possible inspiration for Chastellux’s preposterous claim.

The myth persists

Beyond the Revolutionary era, myths of a founding-era alternative national language continued to capture people’s imagination. A brief study of Chastellux written during the Holocaust vividly imagined the counterfactual scenario of a Hebraic or Germanic founding language: “It would be interesting to speculate about the effect on Hitler of an America which spoke Hebrew … or about the changes in subsequent history which might have been wrought by the establishment of German as a coordinate language in America.”

As recently as 2023, the Armstrong Institute of Biblical Archeology peddled a bizarre version of the myth in which the Pilgrims “came within one vote of adopting Hebrew as the official language of Plymouth Colony.”

The persistence of these linguistic myths reflects enduring anxieties about national identity and cultural heritage in the United States. These polemical, imaginative, and satirical stories probe the question of what it means to be American – or Jewish – within a global, multicultural context.

Most remarkably, Chastellux’s idea uncannily came true in the modern State of Israel, where a revivified spoken Hebrew now serves as the official government language.

The notion of an almost-Hebraic America, much like Trump’s executive order, highlights how language serves as both a symbol of national unity and a source of ongoing cultural debate.

This article was originally published by RealClearHistory and made available via RealClearWire.

Israel Benporat serves as a lecturer at Yeshiva University’s Straus Center for Torah and Western Thought and is a fellow with the Jack Miller Center. He holds a PhD in history from CUNY Graduate Center.

-

Civilization5 days ago

Civilization5 days agoThe Theory and Practice of Sanctuary Cities and States

-

Civilization5 days ago

Civilization5 days agoAmerica Can’t Secure Its Future on Imported Minerals

-

Civilization5 days ago

Civilization5 days agoCompetition Coming for the SAT, ACT, AP, and International Baccalaureate

-

Civilization3 days ago

Civilization3 days agoThe Minnesota Insurrection

-

Civilization3 days ago

Civilization3 days agoSupreme Court Orders CA Dems To Justify Prop 50 Maps

-

Education2 days ago

Education2 days agoFree Speech Isn’t Free and It Cost Charlie Kirk Everything

-

Civilization2 days ago

Civilization2 days agoThe Campaign Against ICE Is All About Open Borders

-

Executive2 days ago

Executive2 days agoWaste of the Day: U.S.-Funded International Groups Don’t Have to Report Fraud