Civilization

The Snatch and Grab of Maduro Was Not ‘Illegal’

President Trump has ample statutory and case-law support for capturing Nicolas Maduro as he did, as the Noriega precedent makes clear.

The world woke up Saturday morning January 3, 2026, to the news that the United States launched a special operations mission into Venezuela, and successfully captured Nicolas Maduro and his wife, Cilia, and brought them to New York to stand trial on various drug and weapons charges.

Maduro and his false pleas

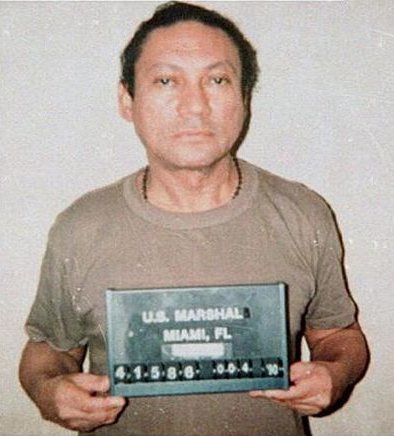

Before the aircraft carrying the two fugitives touched down in NY the “experts” in the media were analyzing the legality of the U.S. operation. Predictably, Democrat leaders charged that President Trump had violated international law by invading a sovereign nation and kidnapping the head of state. Republican supporters claimed the operation was a legitimate law enforcement operation supported by the U.S. military and offered the example of the capture of Manuel Noriega in Panama in 1989 as proof that laws were not violated.

The debates were heated but unenlightening. They sounded more like 8-year-olds arguing “is to,” “is not” trying to settle a school yard dispute.

The Maduro operation raises issues that were addressed in the Noriega capture and the ensuing criminal prosecution of the Panamanian dictator in U.S. Federal court. Fortunately, the court decisions in the Noriega matter provide precedent and should govern the Maduro case.

Extradition Treaty

Maduro may claim that a military operation to snatch him from his own country and bring him to the United States to face trial was illegal because the U.S. had an extradition treaty with Venezuela and did not invoke that legal process. The U.S. and Venezuela did sign an extradition treaty in 1922, but Article VIII of the treaty provides that neither party is required to extradite its own citizens to the other country to face criminal trial. Clearly, extradition was not an option in Maduro’s case.

But doesn’t that mean he is safe from the reach of U.S. justice if he remains in is home country? The short answer is, No.

In 1992 the Supreme Court considered “whether a criminal defendant, abducted to the United States from a nation with which it has an extradition treaty, thereby acquires a defense to the jurisdiction of this country’s courts.” The Court said no and held that the defendant, who was abducted from his home country of Mexico, was subject to the criminal jurisdiction of U.S. courts. The applicable U.S.-Mexico extradition treaty, like the U.S.-Venezuelan treaty, did not require a country to turn over their own citizens.

Noriega raised the same issue to contest U.S. jurisdiction over him and the United States Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit, relying on the 1992 SCOTUS precedent, rejected the argument.

Head of State Immunity

As early as 1812 the Supreme Court recognized the United States followed the common international understanding that the scope of a country’s criminal jurisdiction was determined by the country and was not susceptible to diminution by any outside authority. As that doctrine developed over time, the nations of the world generally followed the principle that the head of a sovereign nation was immune from prosecution for violating the laws of another nation in which he happened to be present.

The analogous application of this principle is the doctrine of diplomatic immunity. Countries around the world generally accept the principle that the best way to protect their own diplomats from criminal liability in the countries in which they are assigned is to offer that same courtesy to foreign diplomats on its soil. But this principle applies because the host country determines to apply it, not because it is imposed by some higher authority. “International law” does not dictate that nations extend such comity to other nation’s diplomats. Each nation chooses to do so.

Maduro cannot claim such immunity under U.S. law

While Congress passed the Foreign Service Immunity Act in 1976 and tasked the judiciary to determine whether a given official was entitled to immunity from civil actions, the Act did not address criminal proceedings. Accordingly, whether a foreign national is entitled to immunity from criminal prosecution is determined by Executive branch officials, not judges. In Maduro’s case, the United States did not recognize him as the legal and legitimate president of Venezuela and he is not entitled to claim head of state immunity.

Noriega found himself in the same boat, so to speak, and his claim of head of state immunity was denied. Maduro’s claim is even weaker. Not only the United States, but Canada, the UK, the European Union, and a host of Latin American countries refused to recognize Maduro’s claim to the presidency. Accordingly, if the rule of law applies in his case and the court defers to the Executive branch determination that Maduro was not the legitimate president of Venezuela, his claim of immunity will be denied.

Due Process

According to published reports, Maduro and his wife were snatched from their compound during the early morning hours of January 3 and taken against their will to a U.S. warship off the coast of Venezuela and then transported by U.S. aircraft to NY where they were processed into a detention facility to await their day in court. The forcible and involuntary removal of he and his wife, he will probably argue, violate due process and shocks the conscious.

Unfortunately for Maduro, the law has long been settled that “the power of a court to try a person for crime is not impaired by the fact that he had been brought within the court’s jurisdiction by reason of a `forcible abduction.”

Noriega made the same claim, and it was also rejected. And the facts surrounding Noriega’s abduction were, arguably, far more disruptive, intrusive, and invasive than Maduro’s.

Operation Just Cause was launched by President George H.W. Bush on December 20, 1989, and involved over 26,000 U.S. troops. The initial assault targeted Panamanian defense forces, supply depots, airfields, and other military installations. Resistance by the Panamanian Defense Force was stiff over the first three days. Twenty U.S. service members were killed in action and another 300 wounded. Several hundred Panamanian military and civilians lost their lives in the fighting. It was an invasion by a large military force.

Maduro v. Noriega

Noriega eluded capture initially and took refuge in the Vatican Embassy. He finally surrendered to U.S. forces on January 3, 1990, and was taken to the U.S. to face trial. The U.S. military occupied Panama until late January when an interim Panamanian government was able to take control of a stabilized country.

The Maduro raid, on the other hand, was over in less than three hours. While military targets were assaulted by U.S. aircraft to provide security for the military and law enforcement personnel tasked with capturing Maduro and his wife, the operation was more like a sophisticated SWAT take down of a large criminal enterprise than a military invasion. Instead of 26,000 troops invading like in Panama, current reporting puts the total number of U.S. troops involved in Operation Absolute Resolve at around 200. The number of U.S. troops who actually set foot on Venezuelan soil was probably less. Unlike Panama, no U.S. military assets remained in Venezuela after the extraction of Maduro and his wife. No U.S. troops were killed and only a handful were wounded. Early estimates of Venezuelan casualties range between 40 and 80 killed. Reports indicate that many of the casualties were Cuban security personnel detailed to provide personal protection for Maduro.

Presidential succession already in train

After capture and removal, the Venezuelan Supreme Court issued an order declaring Executive Vice President Delcy Rodriguez, who was appointed by Maduro, to be the temporary president under Article 234 of the Venezuelan constitution. She will serve as president for 90 days and the National Assembly may extend it for another 90 days. If Maduro’s unavailability continues beyond 90 days the National Assembly has the power to declare his unavailability “permanent” and call for elections within 30 days.

If the invasion of Panama did not provide Noriega with a viable legal defense to U.S. criminal jurisdiction, it is highly unlikely that a court, consistent with legal precedent, will find Maduro has a valid due process claim.

UN Charter

Article 2(4) of the UN Charter provides, “All Members shall refrain in their international relations from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state, or in any other manner inconsistent with the Purposes of the United Nations.”

The UN Charter does not provide Maduro with a personal defense to the criminal charges against him or limit the jurisdiction of U.S. courts over him. It is, however, a treaty signed by the United States, ratified by the Senate, and under the Supremacy Clause of the Constitution is part of the “supreme law of the land.”

The Supreme Court has held, however, that treaties like the UN Charter are not self-executing and are not “domestic law” unless Congress passes separate enabling legislation or the language of the treaty makes it self-executing. Congress has not passed legislation applicable to Article 2(4) and nothing in the language of the Charter indicates that it is self-executing. Accordingly, a claim by Maduro that the U.S. cannot assert criminal jurisdiction over him because he was extracted involuntarily by military force from Venezuela will fail.

But what about the broader application of Article 2(4) in the community of nations? Was the U.S. raid to capture Maduro illegal under international law because it allegedly violated Article 2(4)?

The UN Charter doesn’t necessarily apply

“Experts” have and will continue to give their opinions, but there is no final authority with binding jurisdiction to decide the issue and render a final judgment on the matter. The jurisdiction of the International Court of Justice (ICJ), the tribunal created by the UN Charter to rule on such matters, is dependent upon the consent of the parties. Member nations are not compelled to submit to the ICJ’s jurisdiction. The U.S. has not consented to ICJ jurisdiction and the ICJ has no jurisdiction to adjudicate the legality of the U.S. operation.

The result is that opinions on the legality of the raid under the UN Charter are just that, opinions of individuals who have no independent authority to determine international law questions. Of course, if a majority of the House of Representatives believe the raid violated Article 2(4) they could pass a Resolution of Impeachment. The issue would then move to the Senate to determine whether the raid was a “high crime or misdemeanor” sufficient to warrant impeachment of the President and, if so, whether the raid violated Article 2(4). If two-thirds of the Senate agrees, a conviction would remove the President from office.

In other words, whether the Maduro raid was “illegal” under international law is really a domestic political question beyond the jurisdiction of any court or tribunal with final judgment authority over U.S. officials or institutions.

Meanwhile, Maduro would most likely be serving a lengthy sentence of incarceration.

Congressional Notification

Much of the political debate over the Maduro raid has centered on the Trump administration’s failure to notify Congress of the raid before it began. The applicability of the War Powers Resolution (WPR) and whether the President is required to notify Congress before taking such actions is a political question; it does not provide Maduro with a defense to the criminal charges against him.

It is important to note that neither the WPR nor the Constitution explicitly requires the President to consult with or notify Congress before undertaking a military operation that will put U.S. forces in harm’s way. Section 3 of the WPR does require the President “in every possible instance” to consult with Congress before sending troops into hostilities. In this instance, however, the administration claims that prior consultation was not possible due to the weather conditions and the timeliness of the intelligence upon which the success of the mission depended. And, of course, there was concern over security leaks that could compromise the safety of American forces and hinder the success of the mission.

The WPR also requires the President to notify Congress within 48 hours of the operation’s launch and withdrawal of all U.S. forces within 60 days unless Congress approves of a longer engagement. It appears that all U.S. forces have already been withdrawn.

Courts have never decided

President Bush notified Congress a couple of hours before the Panama invasion began and gave Congress official notice “consistent” with the WPR after the fact. Presidents Clinton and Obama followed a similar practice of providing notice to Congress within 48 hours of using military force but took pains to avoid acknowledging that the WPR limited Executive authority under Article II of the Constitution.

The political debate will continue as long as there are Democrats in Congress and a Republican in the White House, or vice versa. Presidents of both parties have refused to acknowledge that the WPR limits the Presidents Article II powers. When asked to rule on the constitutionality of the WPR, federal courts have uniformly declined to decide the issue. That debate will continue between the Executive and Legislative branches, but it will not impair the prosecution of Maduro and his wife.

Conclusion

Under existing U.S. law and precedent, Maduro has no viable claim that U.S. criminal courts lack jurisdiction over him for the crimes alleged in the indictment. Political disputes between supporters and opponents of President Trump over the wisdom and “legality” of the operation will continue well into the future. How those will be resolved will depend, as it should, on the outcome of elections and who the American people decide to put in charge. International tribunals do not have authority to determine that question.

One important question that remains unaddressed thus far is why prosecute Maduro in NY? Noriega was indicted and tried in Miami, Florida. The decision denying Noriega’s challenges to U.S. jurisdiction and affirming his conviction was from the United States Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit, the regional appellate court with jurisdiction over Florida. The Supreme Court denied Noriega’s petition for certiorari. One wonders why the Justice Department is bringing the case in NY where recent experience with courts and juries should raise concerns when the case deals with something in which Donald Trump has been involved. Time will tell.

This article was originally published by RealClearDefense and made available via RealClearWire.

William A. Woodruff is a retired Army lawyer who, as Chief of the Army Litigation Division, was responsible for defending Army policies, programs, and operations in federal courts around the country. He retired from active duty in 1992 and taught law for 25 years at Campbell University School of Law in North Carolina.

-

Civilization4 days ago

Civilization4 days agoVirginia redistricting – the forgotten theater

-

Civilization8 hours ago

Civilization8 hours agoThe U.S. and Australia Must Lead the Critical Minerals Race

-

Civilization4 days ago

Civilization4 days agoWhat the Political Attacks on Fetterman Reveal

-

Clergy4 days ago

Clergy4 days agoDecapitating Amalek: Iran, Purim, and the Obligation to Act in Time

-

Education20 hours ago

Education20 hours agoWaste of the Day: Boston’s Soccer Stadium Cost Almost Tripled

-

Civilization3 days ago

Civilization3 days agoIran: A Humbling Reminder of the Public Square We Take for Granted

-

Executive3 days ago

Executive3 days agoWaste of the Day: Rhode Island Overtime Payments Approach $300,000

-

Civilization1 day ago

Civilization1 day agoU.S.-Israel Joint Action Against Iran Is Just and Necessary