Executive

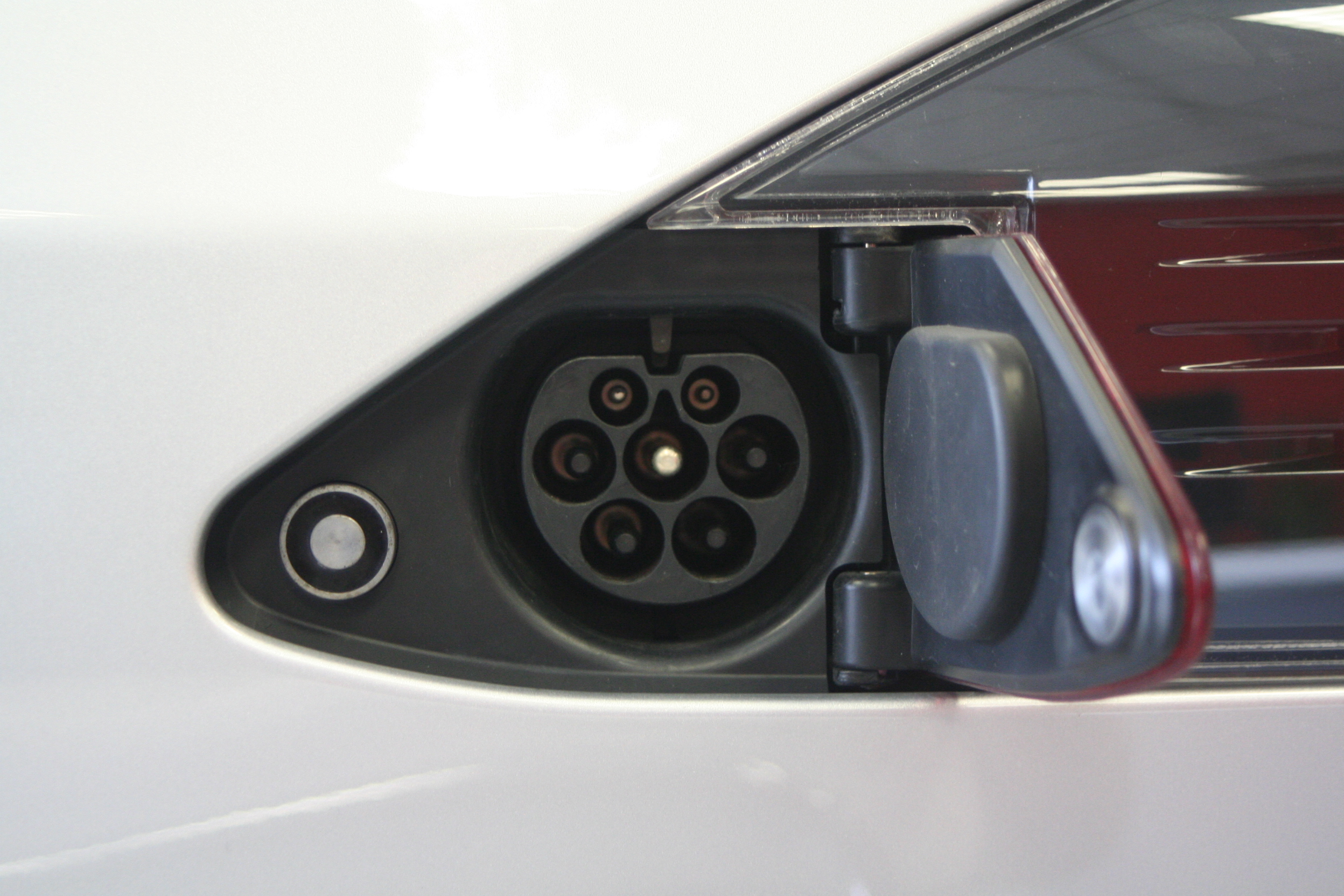

Mega-Jolt: The Costs and Logistics of Plugging in EVs Are About to Become Supercharged

EV charging stations – and the power plants to juice them – will be the weak link in the government’s attempt to electrify the car fleet.

U.S. Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm gave Americans an unintended glimpse of the future during her road trip this summer touting the wonders of electric vehicles. Her public relations misadventure in Georgia involved one of her staff in a gasoline-powered vehicle blocking off a coveted charger in advance of her arrival, leading to frayed tempers and a local EV owner calling the cops. It was an illustration of the challenges drivers could face as governments push the public to embrace plug-in vehicles.

Hyped as technological marvels, EVs are boobytrapped with a host of inconveniences and tradeoffs. By now many people have heard about range anxiety, exploding lithium-ion batteries, and the environmental destruction caused by global mining for battery minerals.

But more challenges are in the offing as the federal government and the states pump in billions of dollars to build a massive national infrastructure of charging stations to power the EVs.

EV sales are creeping up, but nowhere near the ambitious targets set by the policy experts, accounting for under 8% of new car sales in the third quarter, and rising to nearly 10% in September. California stands at the vanguard of the nation’s EV transition, with more than 1 million electric vehicles among the state’s 31-million-plus registered vehicles, and EVs accounting for about 25% of new car sales in the second quarter.

At some point, EV experts promise, the kinks will get worked out, and EVs will become as convenient as smartphones. But at present, the EV industry has a classic chicken-and-egg problem on its hands. The current demand for EV charging does not economically justify rapidly expanding the nation’s charging infrastructure, but without an expanded charging infrastructure in place, most people won’t buy EVs for fear of being stranded.

Despite California’s massive infrastructure investment, now totaling nearly 94,000 public chargers, the state has fallen behind its goal of 250,000 public chargers by 2025 – and potentially 10 times that number by 2035, when the ban on new gasoline-powered cars takes effect.

There’s no consensus on the amount of public chargers that will be needed. According to a California Energy Commission assessment, California will need more than 2.4 million public chargers to accommodate about 15.5 million electric cars, trucks, and buses by 2035. That breaks down to 2.11 million chargers (including 83,000 fast chargers) to support 15.2 million electric cars, as well as 256,000 depot chargers and 8,500 public chargers for 377,000 trucks and buses.

The 2.4 million chargers would serve only half the registered vehicles in the state. Many more will be necessary to complete the second half of the transition, from 15.5 million EVs to more than 31 million EVs by mid-century. Those chargers will have to be installed at curbsides, parking lots, parking decks, grocery stores, restaurants, convenience stores, big box stores, office buildings, strip malls, shopping centers, movie theaters, and other locations so that drivers always have ready access to plug-in.

By comparison, California now has about 11,000 gas stations, convenience stores, and other businesses that sell gasoline, which translates to about 110,000 individual gas nozzles, according to an estimate by Jeff Lenard, vice president of Strategic Industry Initiatives at the National Association of Convenience Stores. That means the transition from fossil fuels to electrons will require California to install at least 20 EV charging ports for every gas nozzle by 2035.

Not all chargers are equal, so the new EV infrastructure will require significant changes in driving habits. While so-called fast chargers can bring a battery to 80% of capacity in under an hour, most of the new public chargers will be cheaper, Level 2 technology, which provides between 5 miles and 60 miles of range for each hour of charging and isn’t practical for charging up quickly on a road trip.

Chargers are expected to lose money until there are enough EVs on the road to justify the investment. The cost of building a fast-charging station with four or more charging ports can range from several hundred thousand dollars to more than $1 million. Reliability remains a persistent problem, one that will shadow the industry as chargers are built out in remote areas, low-income areas, and other out-of-the-way places.

In the meantime, Analytics firm J.D. Power says that 20% of all EV drivers reported visiting a charger that did not or could not charge because it wasn’t working or there were long lines. The dissatisfaction rates ranged from 12% in the Cleveland-Akron-Canton area to 35% in South Florida. The firm said the trend is moving in the wrong direction: as more people buy EVs, “overall satisfaction continues to decline.”

This year, a Los Angeles Times columnist declared she’s ready to trade in her EV because charging is such a hassle. She wrote that chargers are sometimes blocked by cars that aren’t charging, exposed to blistering sunlight, charging at lower levels than advertised, or “it may shut off mid-charge with no warning or reason.”

The frustration seems to have no expiration date. And it includes a problem not caused to technology or economics but by human nature: vandalism. As Jonathan Levy, EVgo chief commercial officer, told the New York Times last year: “Where there’s a screen, there’s a baseball bat.”

This article was adapted from a RealClearInvestigations article published October 24.

This article was originally published by RealClearPolicy and made available via RealClearWire.

John Murawski reports on the intersection of culture and ideas for RealClearInvestigations. He previously covered artificial intelligence for the Wall Street Journal and spent 15 years as a reporter for the News & Observer (Raleigh, NC) writing about health care, energy and business. At RealClear, Murawski reports on how esoteric academic theories on race and gender have been shaping many areas of public life, from K-12 school curricula to workplace policies to the practice of medicine.

-

Executive4 days ago

Executive4 days agoSecret Service chief gets no solace

-

Executive3 days ago

Executive3 days agoWaste of the Day: Louisville Taxpayers Pay Nearly $600,000 For Empty Building’s Maintenance, Security

-

Guest Columns4 days ago

Guest Columns4 days agoFear Itself: Democrats’ Favorite Strategy Caused Their Current Chaos

-

Executive3 days ago

Executive3 days agoWhere is Joe Biden – or Jill?

-

Executive1 day ago

Executive1 day agoWaste of the Day: Throwback Thursday: Cities Used Crime Prevention Funds on Soccer Games, Paper Shredding

-

Civilization4 days ago

Civilization4 days agoBuild Iron Dome in the United States To Prepare for Israel’s Worst Day

-

Executive2 days ago

Executive2 days agoFacile and politically motivated suggestions

-

Executive4 days ago

Executive4 days agoThe Emerging GOP Plan To Beat Kamala Harris