Executive

Private Firms, States Use Tobacco Lawsuit Playbook in Energy Cases

The energy industry is the new tobacco industry, with private law firms scoring appointments to represent blue States.

Last September, tens of thousands of climate change true believers marched to protest President Biden’s appearance before the United Nations. Although the Biden administration ushered into law sweeping legislation aimed at combating global warming and earmarked tens of billions of dollars for alternative energy ventures, the demonstrators were not appeased.

A demand to end energy from fossil fuels

Their objective, spelled out in placards, is as specific as it is drastic: “End Fossil Fuels.” The demand is for Western nations to immediately ban any new oil and gas extraction projects.

In Europe and the United States, these eco-activists have issued apocalyptic warnings about global warming while leveling threats against election officials, corporations, and entire industries. Some of them commit unconnected acts of vandalism ranging from desecrating priceless European works of art and smashing the Magna Carta to storming the court during the finals of the U.S. Open tennis tournament and disrupting professional golf tournaments.

Other actions are more on point – and more disruptive and dangerous. Protesters have chained themselves to the White House gates, tied up traffic in New York City, London, and Washington, blocked bridges, and sabotaged oil pipelines. The perpetrators of such measures (and their sympathizers) describe such methods as “direct action.” Critics use a different term. They call it “eco-terrorism.”

However they are characterized, such antics serve mainly to alienate the public. But a far more potent weapon is being deployed against energy companies: A cadre of liberal lawyers, environmental activists, and attorneys general from Democratic states and municipalities are systematically suing energy companies and demanding multibillion-dollar payouts. Their efforts have not risen to a top-tier concern in American politics, but that is about to change: The latest iteration of “lawfare” is now fully deployed and expected to reach critical mass in 2025.

A coordinated litigation strategy

These well-funded lawsuits, and there are now more than 30 of them, are not equivalent to throwing a can of soup at an art masterpiece. The coordinated litigation strategy is nothing less than an attempt to throw a monkey wrench into the industry that makes modern life possible – that heats and cools Americans’ homes and offices, supplies gasoline for transportation and agriculture, and powers the nation’s electric grid.

“In politics, it’s all about who can tell the best story – and the environmental movement tells a compelling story about the costs of climate change,” says Wayne Winegarden, a senior fellow at the Pacific Research Institute, a think tank that supports free market solutions to global warming and other environmental issues. “But the hope that we can run the economy on solar and wind is delusional. We simply don’t have an economy without oil.”

“And it’s not just energy,” Winegarden adds. “Some 6,000 different products are oil derivatives, many of them essential to everyday life.”

Those commodities range from solvents, motor oil, antifreeze, housepaint, linoleum, and synthetic rubber to heart valves, dentures, eyeglasses, cortisone, artificial limbs, car battery cases, vinyl records (and else anything made of vinyl), and basically all plastic products.

No workable alternative to energy from fossil fuels

Climate change activists acknowledge the point while also maintaining that benign substitutes can be found for plastics and other materials, or that exceptions could be made for essential products. What they won’t acknowledge is that when it comes to energy, the reality seems to be – at least for now – that the country (and the world) is dependent on fossil fuels.

The energy mix is always changing. Twenty-five years ago, coal-burning power plants produced slightly more than half this nation’s electricity. Today, it’s less than 18% and falling. When America’s total energy needs are added up, coal is down to 9% – the same as renewable sources and nuclear power. But petroleum (38%) and natural gas (36%) are indispensable.

Nonetheless, the lawyers, activists, and like-minded politicians leading the global effort against fossil fuels make no apologies. Quite the opposite: U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres has repeatedly condemned the industry. Earlier this year, he called the fossil fuel industry the “godfathers of climate chaos” while urging governments to find an exit ramp off “the highway to climate hell.”

Writing in the journal BioScience, a group of the world’s leading climate experts recently issued yet another dire warning. “Much of the very fabric of life on Earth is imperiled,” they wrote. “We are stepping into a critical and unpredictable new phase of the climate crisis.”

A partisan election issue in the United States

In the United States, these issues have a strong partisan component. Democrats favor tighter environmental rules and have appropriated vast sums of public money to research and produce renewable sources of energy. Republicans tend to be in the other camp. Although in the last weeks of the 2024 campaign, Donald Trump stopped calling global warming “a hoax,” he has reprised Sarah Palin’s “Drill, Baby, Drill” mantra to enthusiastic responses from his audiences.

The most noticeable environmental wedge issue in this campaign has been hydraulic fracturing (usually just called “fracking”), a process that entails drilling deep into the earth and pumping a high-pressure mixture of water, sand, and chemicals to forcibly release the gas embedded in layers of rock. Until relatively recently, natural gas was hailed as an eco-friendly alternative to coal and oil. No longer. When Kamala Harris first ran for president four years ago, she said there was “no question” that she would seek a federal ban on fracking.

Climate change an existential threat? Really?

Joe Biden, the winning Democratic Party candidate in 2020, wouldn’t go that far – and Harris acquiesced to his policies after being chosen as his running mate. The issue resurfaced this summer after Harris became the nominee, with Republicans believing her past antipathy to fossil fuels is a winning one for them, particularly in Pennsylvania. Some environmental activists think Trump supporters might be reading the wrong tea leaves. As environmental writer William McKibbon noted in the pages of The New Yorker, in the waning days of the 2020 campaign against President Trump, Biden called global warming “an existential threat to humanity” while vowing to end federal subsidies for the oil industry.

“We have a moral obligation to deal with it,” Biden added during his last debate with Trump, “and we’re told by all the leading scientists in the world we don’t have much time.” This comment set off an interesting exchange.

TRUMP: “Would you close down the oil industry?”

BIDEN: “I would transition from the oil industry, yes.”

TRUMP: “Will you remember that, Pennsylvania?”

As Bill McKibben noted, 12 days after the election, Joe Biden carried Pennsylvania and, with it, the presidential election. McKibben’s point is that public opinion may be shifting. Yet even by 2020, another front in the war against fossil fuels had been opened. The venue was no longer solely the ballot box.

It was also the judicial system.

Money Talks

The first spate of lawsuits against oil companies for offering their products on the open market was filed in 2017 in California state courts. The plaintiffs were eight coastal cities and counties (San Francisco, Oakland, Santa Cruz, Richmond, Imperial Beach, and the counties of San Mateo, Marin, and Santa Cruz). The defendants were Shell Oil, Chevron, ExxonMobil, and more than two dozen other energy companies. The identical language in the cookie-cutter lawsuits began with a rousing indictment of the entire industry:

Defendants, major corporate members of the fossil fuel industry, have known for nearly a half century that unrestricted production and use of their fossil fuel products create greenhouse gas pollution that warms the planet and changes our climate. They have known for decades that those impacts could be catastrophic and that only a narrow window existed to take action before the consequences would not be reversible. They have nevertheless engaged in a coordinated, multi-front effort to conceal and deny their own knowledge of those threats. … At the same time, Defendants have promoted and profited from a massive increase in the extraction and consumption of oil, coal, and natural gas, which has in turn caused an enormous, foreseeable, and avoidable increase in global greenhouse gas pollution and a concordant increase in the concentration of greenhouse gases, particularly carbon dioxide (“CO2”) and methane, in the Earth’s atmosphere. Those disruptions of the Earth’s otherwise balanced carbon cycle have substantially contributed to a wide range of dire climate-related effects, including global warming, rising atmospheric and ocean temperatures, ocean acidification, melting polar ice caps and glaciers, more extreme and volatile weather, and sea level rise.

In April 2018, two Colorado jurisdictions, San Miguel County and the city of Boulder, filed suit against ExxonMobil and Suncor (formerly Sun Oil.) Those lawsuits allege that the two companies knew for years that their natural gas facilities and the gasoline it sold to filling stations were contributing to climate change. The claims of actual damages are vague – the suit suggests, without explicitly saying how, that warmer temperatures will mean lower snowpack in the mounts and, thus, less water for the rivers below. By that logic, any state, city, or country in the country could sue any oil company operating in the country, which is the idea.

“Money talks,” said Richard Wiles, an activist who formed a group that encourages such litigation. “If New Jersey has a multibillion-dollar decision against Big Oil, why wouldn’t North Carolina say, ‘Damn!’?”

More lawsuits against energy companies

As if on cue, four months after the two Colorado lawsuits, the city of Baltimore and the state of Rhode Island filed nearly identical suits against two dozen energy companies, alleging their “wrongful conduct” would cause “flooding and storms [to] become more frequent and more severe, and average sea level will rise substantially along [the] coast…”

In 2019, Massachusetts filed a similar case. This was followed in 2020 by Delaware, Connecticut, Minnesota, Washington, D.C., Charleston, S.C., Hoboken, N.J., and the Hawaiian cities of Honolulu and Maui. In 2021, the state of Vermont, New York City, Annapolis, and Anne Arundel County, Maryland, joined the parade. The rush was on. The Big Kahuna was always going to be California; and on Sept. 15, 2023, five months after Gov. Gavin Newsom appointed Rob Bonta attorney general, Bonta’s office did just that.

For more than 50 years, Big Oil has been lying to us – covering up the fact that they’ve long known how dangerous the fossil fuels they produce are for our planet. It has been decades of damage and deception. Wildfires wiping out entire communities, toxic smoke clogging our air, deadly heat waves, record-breaking droughts parching our wells. California taxpayers shouldn’t have to foot the bill. California is taking action to hold big polluters accountable. Gov. Gavin Newsom (D-Calif.)

Bonta’s public statements mirrored the language of the California lawsuits – all the litigation, really – by stressing what the plaintiffs have characterized as the energy companies’ deceptions about the effects of fossil fuels on the Earth’s climate.

“This much is clear: Big Oil continues to mislead us with their lies and mistruths, and we won’t stand for that,” Bonta said last year while filing the suit. “We will continue to vigorously prosecute this matter and ensure that Big Oil pays to abate the harm they have caused, and we will recover ill-gotten gains that will benefit Californians.”

A contrived argument that energy companies knew the “damage” they were “doing”

In other words, a primary rationale for all this litigation is that energy companies were allegedly saying one thing privately regarding the impact of greenhouse gases and another publicly. This was a political ploy as well as a legal strategy. But there are discordant elements to this argument, which lawfare critics assert is a contrivance – and a misuse of the judicial system.

For starters, whatever oil company employees may have said or done to bolster their industry is one of the least compelling aspects of the intense, worldwide, decades-long, disputation over global warming. Yes, the industry tried to put the best face on things, but to little effect: The debate has been utterly dominated by fossil fuel’s critics for years.

Second, if the language of these lawsuits sounds derivative, that’s because it is: The plaintiffs have made no secret that their public relations approach, their legal strategy, and even the wording of the legal complaints are cloned from the great tobacco litigation of the 1990s.

Third, the defendants not only marketed a perfectly legal product in the exact manner advertised; they sold a product the public was demanding. Certainly, no one (especially in California, where smog has been an issue since the 1940s) believed that the exhaust fumes from internal combustion engines were good for the air quality or the climate. The problem was that no viable alternative existed at the time.

“Misinformation” – oh, that word

Although these lawsuits claim that the misinformation – yes, they use that word – put out by the fossil fuel industry delayed the implementation of alternative energy, that’s speculative and dubious. It’s also an onerous legal burden to lay on companies run by previous generations of executives. Energy company employees who may have minimized the harmful environmental impacts of fossil fuels three decades ago are mostly deceased or retired now.

Not to sound flip, but those who are still alive are enjoying their beach houses in some of the same communities that are now suing their old employers. A multitrillion-dollar transfer of wealth (Charleston, S.C., alone is asking for $2 billion in damages) won’t alter their lives: The costs of any payouts (and the cost of the ongoing litigation as well) will be borne by today’s energy consumers, and those in the future.

This would mean, if this litigation succeeds, that nearly everyone in this country will pay significantly more at the gas pump and for electricity in what will essentially be a tax imposed by the judicial branch. It’s a highly regressive tax that will hit working-class Americans the hardest.

“Every Newspaper in America”

In 1976, a subcommittee of the House Committee on Science and Technology held hearings into legislation called The National Climate Program Act. The Senate did so the following year, which is when a young newspaperman whose father had been in the Senate was elected to a seat in Congress. His name was Albert Gore Jr.

The environment was one of young Rep. Al Gore’s passions, and he arrived on Capitol Hill with a specific interest in global warming. In 1981, he and Rep. James Scheuer of New York organized a hearing featuring famed oceanographer Roger Revelle, co-author of an influential 1957 paper postulating that – contrary to conventional wisdom – the Earth’s oceans could not absorb the greenhouse gases being produced by an industrialized world. The rest, he wrote, would bounce back into the atmosphere.

This is believed to have been the first congressional hearing on global warming. The following year, Gore led another hearing, this one featuring James E. Hansen, the scientist who headed the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies. Hansen told Congress that his agency’s data suggested that Earth had warmed 0.7 degrees Fahrenheit over the previous century

Seven years later, on June 23, 1988, Hansen was back for another Senate hearing, this one organized by Colorado Democratic Sen. Tim Wirth. This session changed everything. Testifying before the Committee on Energy and Natural Resources, Hansen got right to the point.

Mr. Chairman and committee members, thank you for the opportunity to present the results of my research on the greenhouse effect which has been carried out with my colleagues at the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies.

I would like to draw three main conclusions. Number one, the earth is warmer in 1988 than at any time in the history of instrumental measurements. Number two, the global warming is now large enough that we can ascribe with a high degree of confidence a cause-and-effect relationship to the greenhouse effect. And number three, our computer climate simulations indicate that the greenhouse effect is already large enough to begin to affect the probability of extreme events such as summer heat waves.

The globe is warming, the globe is warming! Stop using energy!

Several senators on the committee had already read Hansen’s report, but still found it bracing to hear him say it aloud. Sen. Dale Bumpers of Arkansas, a man then believed to harbor presidential ambitions, said Hansen’s warning should be “cause for headlines in every newspaper in America tomorrow morning.” Bumpers wasn’t far off. The New York Times led the way. Its Page One headline, placed prominently above the fold, blared, “GLOBAL WARMING HAS BEGUN, EXPERT TELLS SENATE.”

Al Gore’s own 1988 presidential campaign had fizzled by then, but he was already at work on a book, “Earth in the Balance,” that would not only be a runaway best-seller, but would also re-inject him into the national political conversation. It helped make him Bill Clinton’s 1992 running mate. By then, an even more influential book, “The End of Nature” by renowned environmental writer Bill McKibben, had altered the national conversation.

The anti-energy documentary

One more signpost: In 2006, having served two terms as vice president and narrowly losing the 2000 presidential race, Al Gore starred in a blockbuster documentary film, “An Inconvenient Truth,” that garnered not only an Academy Award, but also a Nobel Peace Prize.

The point of recounting this history is that the entire world has been on notice about rising temperatures for decades, with fossil fuels invariably cast as the culprit. But this raises obvious questions: Why not sue Detroit’s automakers? Or construction companies that build freeways? Or cities, towns, and states that (still) purchase internal combustion engines for their fleets of police cars, buses, snowplows, and ambulances – and then buy millions of dollars’ worth of gasoline each year from the same companies they are now suing. Why go after this one industry?

At least part of the answer, not surprisingly, is politics.

An Old Playbook

The coordinated effort to use the court system to target energy companies was launched at a workshop in La Jolla, California, in June 2012. Hosted by the Union of Concerned Scientists and the Climate Accountability Institute, the very title of the workshop gave the game away: “Establishing Accountability for Climate Change Damages: Lessons From Tobacco Control.”

By the 1990s, with Bill Clinton and the trial lawyers lobby leading the attack, Big Tobacco had become an easy mark. In 1964, when the U.S. Surgeon General’s report labeled cigarettes a grave health hazard, 42.6% of Americans were smokers. By the end of the 1990s when the mass litigation was settled, that rate was cut in half (and it’s been halved again since then). It’s only a slight exaggeration to say that smoking went from being a sign of sophistication in popular culture to being a signal in any given Hollywood film that the character with the cigarette hanging from his mouth was invariably destined to be humiliated, maimed, or killed.

Big Oil’s reputation followed a parallel track. In the 1920s, when the movie business was getting off the ground, the Los Angeles basin produced 25% of the world’s petroleum. It was a gritty industry, but one with an egalitarian ethos explored on screen in everything from “Giant,” with Rock Hudson, James Dean, and Elizabeth Taylor, to “The Beverly Hillbillies.”

Oil, and energy from it, loses its luster

“Oil, motion pictures and real estate were like the trifecta of forces that were attracting migrants to come west to L.A.,” said Southern California historian Becky Nicolaides. “Oil was kind of right up there with the glamour of Hollywood.”

This, too, changed – first with the oil shocks of the 1970s, coupled with the founding of the OPEC oil cartel, and then exacerbated by various oil spills. Democrats at the time (as they do today) liked to accuse oil companies of price-gouging. Leading the fight was Sen. Henry Jackson of Washington state, a Democrat who tried to parlay his attacks on oil executives into a 1976 presidential campaign. As environmental awareness took hold, petroleum producers took the hit. In the movies, oil executives were routinely portrayed as murderous villains.

The upshot is that being demonized for decades took its toll. By the time of the 2012 La Jolla conference, climate change warriors like Gore, McKibben, Hansen, and science historian Naomi Oreskes had replaced in the popular imagination once-admired real life oil barons like John D. Rockefeller and T. Boone Pickens, Texas “wildcatters” like Glenn McCarthy (or George H.W. Bush), and swashbuckling industry heroes like oil well firefighter Red Adair.

Fewer jobs at stake

To top it off, in recent years increased industry automation has meant fewer jobs, which gives the industry less political cover than when it was a major employer. Today, even as the U.S. pumps more oil and gas than at any time in history, oil field jobs decline each year. “You just need fewer workers to produce more oil,” Greg Upton, executive director of LSU’s Center for Energy Studies, told Politico. “When you need less workers, that’s a sign of growth. On the other hand, these are real people losing their jobs.”

So the table was set to turn the oil and gas industry into Big Tobacco. Notwithstanding the industry’s reduced popularity, the comparison is quite a stretch. Simply put, no one ever needed a cigarette, unless maybe they were being marched to their own execution. By contrast, nearly everyone on this planet needs access to energy.

The elements of a lawfare strategy

In the Honolulu case, a Chamber of Commerce group led by former Attorney General William Barr made this very point. In a friend-of-the-court brief, Barr wrote, “Humans don’t use fossil fuels because of a ‘public relations campaign.’ They use fossil fuels because they are necessary to the technologies that underlay global human prosperity …”

The attendees at the La Jolla conference anticipated such blowback. In 2012, as they brainstormed how to take on major oil companies, one major takeaway was the need to find receptive audiences and venues. In a post-workshop report, they wrote, “First, any legal strategies involving court cases require plaintiffs, a venue, and law firms willing to litigate – all of which present significant hurdles to overcome.”

But overcome them they did, at least in state courts.

Follow the Money

Finding lawyers did not prove to be difficult. Once the California Coastal Commission filed their lawsuit – and state courts didn’t toss them out – Democratic attorneys in other places started lining up to get in on the action. Their efforts have been supplemented by a private law firm, Sher Leff.

Founded in San Francisco in 2003, the firm was led by principal litigator Vic Sher. Its primary focus was representing public water agencies in lawsuits against industries and manufacturers responsible for polluting drinking water sources with toxic chemicals. It gained recognition for securing hundreds of millions of dollars in damages in cases against major energy companies.

In one major case, New Hampshire v. ExxonMobil, the state, along with Sher Leff, sued multiple oil and gas companies for contaminating the state’s groundwater with a toxic compound. Several companies settled for over $130 million, and the New Hampshire Supreme Court upheld a massive $236 million judgment against ExxonMobil. Of the damages awarded, private attorneys partnering with the state ended up with $27 million in legal fees.

But that case was fought over allegations of specific wrongdoing. The new frontier in climate litigation is to sue the companies for simply doing what they promised to: extracting energy from the ground and selling it. The potential profits for the plaintiff’s attorneys are extraordinary.

Private law firms step in to carry the water

Normally, when a state brings a lawsuit, ethics rules designed to avoid conflicts of interest prohibit its attorneys from profiting personally. But in both the tobacco lawsuits from the 1990s and the current climate cases, private law firms have stepped in to aid the state or city attorneys and are paid through what are called “contingency fees.” This setup allows huge payments to be siphoned off by the private attorneys before the settlement money goes to the state. In the tobacco cases, these fees added up to tens of billions for the law firms involved.

The oil and gas lawsuits are seeking to follow a similar model. Private law firms are teaming up with public attorneys to go after energy companies for damages related to climate change. But unlike the New Hampshire groundwater case, these lawsuits are aiming for compensation for bigger problems, like the damage caused by rising sea levels and extreme weather, all linked to carbon emissions. They are demanding that industry bear the costs of adapting to and mitigating climate change.

Attorneys looking to rake in billions

Just like the tobacco lawsuits, the climate change cases are chasing billions of dollars, but the final numbers are still up in the air since none of these cases have been settled or gone to trial yet. In the tobacco industry’s Master Settlement Agreement, companies agreed to pay $206 billion to states over 25 years, and it’s estimated that around $20 billion of that went to the law firms from the various tobacco lawsuits. The exact breakdown isn’t publicly available, thanks to private arbitration deciding the final figures in most states.

But those who have studied the settlement – even those who pushed for it – have described the attorney’s profits as “obscene.” The payments are still flowing; in 2021 alone, tobacco companies paid states and private attorneys over $6 billion, and excise taxes on tobacco products brought in over $19 billion.

If the climate lawsuits play out similarly, the private attorneys could be looking at contingency fees in the 15%-25% range, which means they could rake untold billions.

Second thoughts

The system of offering large financial rewards to private firms in cases where private monetary incentives aren’t typically involved has raised legal concerns. Peggy Little, senior litigation counsel at the New Civil Liberties Alliance, argues that the contingency fee model doesn’t align with state ethics laws. She told RealClearPolitics that these agreements “violate most state ethics laws because they give the lawyer pursuing the case for the state a direct personal financial interest in the outcome, which no state attorney general could uphold consistent with due process.”

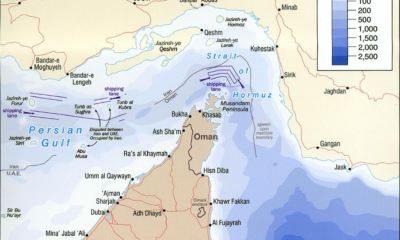

Over the past decade, most lawsuits targeting energy companies have come from liberal state and city attorneys, who have filed in state courts. One case, Sunoco LP et al. v. City and County of Honolulu, Hawaii, is currently before the U.S. Supreme Court. That’s a mixed bag for the climate activists: Honolulu’s damages from global warming are mostly speculative, and the city is 2,500 miles from the nearest oil rig.

Sunoco argues that the Hawaii Supreme Court was wrong to keep the case in state court, claiming that states can’t hold companies liable for the global impact of greenhouse gas emissions.

Meanwhile, 19 Republican attorneys general have asked the Supreme Court to shut down similar lawsuits. They argue that Democratic-led states like California are overstepping by trying to tax or regulate emissions that cross state lines.

Adjusting the argument against the energy companies

In 2021, federal courts addressed this issue in City of New York v. Chevron et al. The Second Circuit ruled that local governments, like cities, counties, and states, can’t use state law to hold multinational oil companies responsible for global greenhouse gas emissions. The court explained that global warming is an international issue, which puts it under the jurisdiction of federal law, not state law. It also ruled that the Clean Air Act gives the Environmental Protection Agency, not the courts, the authority to regulate domestic greenhouse gas emissions.

However, these cases have persisted because Democratic city and state attorneys have since adjusted their argument slightly, claiming instead that the suits are “against certain oil and gas companies that deceived consumers … about the causal relationship between fossil fuel products and climate change.” In the latest cases, they argue that the oil and gas companies had internal reports warning about the possible side effects of fossil fuel consumption but hid, lied about, and misrepresented their internal research findings.

This contention is how Democratic attorneys general are attempting to circumvent the Second Circuit ruling, asserting they do not “aim to impose liability for the production or sale of fossil fuels generally; they instead address local harms resulting from unlawful, deceptive conduct by private defendants.”

Did energy companies hide research?

This approach also mirrors the tobacco lawsuits of the 1990s. In those cases, punitive damages were also imposed after evidence revealed that tobacco companies hid research proving that smoking caused heart disease, lung cancer, and other maladies while publicly denying the risks.

During the 2012 La Jolla workshop, participants discussed the strategy of trying to uncover internal documents to prove deceptive conduct by the oil and gas companies. At the time, they didn’t have the internal documents of the oil and gas companies, but they speculated that similar documents to those uncovered in the tobacco lawsuits “may well exist in the vaults of the fossil fuel industry” that include information about how “the use of their products damages human health and well-being by contributing to ‘dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system.’”

Through the lawsuits, California and others claim they have found documents that prove deceptive conduct. One such report is from the American Petroleum Institute from 1968, which stated, “Significant temperature changes are almost certain to occur by the year 2000, and … there seems to be no doubt that the potential damage to our environment could be severe.”

Waiting for Supreme Court action

California contrasts those internal documents with public statements, including one from an API book titled “Reinventing Energy,” which they quote as saying, “[N]o conclusive—or even strongly suggestive—scientific evidence exists that human activities are significantly affecting sea levels, rainfall, surface temperatures, or the intensity and frequency of storms.”

The Supreme Court has not yet decided whether it will hear Sunoco LP et al. v. City and County of Honolulu, Hawaii or Alabama, et al. v. California, et al. cases. In the Sunoco case, the court has invited the solicitor general’s office to file a brief expressing its views.

Paying the Piper

In the decidedly uninspiring 2024 political campaign, the discourse has ranged from tall tales of immigrants eating cats and dogs, specious comparisons to Nazi Germany, to which side is more guilty of disparaging the other side’s supporters. The topic of crippling lawsuits against energy companies – and who pays if they are successful – has barely been mentioned. That silence doesn’t change the reality that this issue is headed for the U.S. Supreme Court and, depending on its ruling, probably Congress and the White House.

Two public policy issues: The first is that if these suits are successful, who really pays for it? The second is a question of governance. Are class-action suits by plaintiffs’ attorneys and local and state jurisdictions really how the government should make public policy on one of the most far-reaching issues of the age?

Today in Maryland, one of the states suing Big Oil, a pack of cigarettes costs more than $10. It’s a product that costs less than $1 dollar to produce. But the state tax is five dollars, the federal tax is a buck, and the lawsuit settlement adds additional costs, meaning that the tobacco companies’ profit margin is roughly 5%.

Trying to equate energy use to smoking

Nobody pities the poor smoker, because these punitive taxes are aimed, at least in part, in trying to get smokers to quit – for their own health benefit. In other words, lawfare, in this instance, saved lives. Some anti-tobacco voices are candid that this is their goal in the energy lawsuits, too – to make it much less profitable to produce gasoline for our cars, natural gas for our stoves and other usages, and coal-fired electrical power plants. But again, smoking is not equivalent to driving to work, and disadvantaging those who consume energy translates into eroding the economic well-being of all Americans.

Three years ago, as the lawfare effort against energy companies reached critical mass, economist Benjamin Zycher noted that using litigation rather than reaching consensus through normal political channels will result in a decline in energy supply, while putting working-class Americans on the hook for the corresponding costs increases that will naturally follow.

“My conservative estimate of the direct costs of only the electricity portion of a net-zero U.S. energy policy,” Zycher wrote, “is about $500 billion per year, or about $4,000 annually per U.S. household.”

Although the advocates don’t dwell on this scenario, some of them own up to it – and defend it nonetheless.

[I]f you look at other major transformational social change movements like civil rights or marriage equality, they all had a litigation component to them, right? It wasn’t just working for policy change to the Congress. So what this does, what these cases do is open up that flank. We don’t think you can have the climate policy you need for the transition without accountability. Accountability is the first step towards solving climate change. And if we can’t get accountability, it just doesn’t seem like we can really solve this problem. Richard Wiles

An underhanded tax gambit

The 20 Republican attorneys general are unconvinced by this logic. They say environmental activists and their Democratic lawyer allies are using the courts in a fundamentally undemocratic way. If successful, these lawsuits would essentially determine national energy policy through the crude mechanism of tort law while imposing a set of policies – and financial burdens – on the American people that they could never enact through the proper legislative process.

“Consumers are aware of global climate change and continue to use oil,” said Wayne Winegarden. “These lawsuits are an underhanded way of the states throwing on carbon taxes without having to take responsibility for it.”

This article was originally published by RealClearPolitics and made available via RealClearWire.

-

Civilization5 days ago

Civilization5 days agoVance Defends Operation Epic Fury After Years of Opposing Interventions

-

Civilization3 days ago

Civilization3 days agoVirginia redistricting – the forgotten theater

-

Education4 days ago

Education4 days agoWaste of the Day: DEI Contractors Remain in Military’s K-12 Schools

-

Civilization3 days ago

Civilization3 days agoWhat the Political Attacks on Fetterman Reveal

-

Civilization4 days ago

Civilization4 days agoTrump’s SOTU Speech a Win, But It’s Not Enough

-

Civilization4 days ago

Civilization4 days agoAt a Time of International Turmoil, ARC-ES Can Bring Energy Stability to the U.S.

-

Clergy3 days ago

Clergy3 days agoDecapitating Amalek: Iran, Purim, and the Obligation to Act in Time

-

Civilization4 days ago

Civilization4 days agoTop Library Advocate: Backing Drag Queen Story Hour Supports Parental Choice