Constitution

Supreme Court faces supreme test

The Supreme Court has finished its three-day lesson. Now comes the final exam, with the papers due at about the time that final exams run in college. This will be a simple exam, with one question: does the Supreme Court support the Constitution? Or do they support Obama?

The Supreme Court hears argument

The Supreme Court came to the three-day lecture series called “oral argument” after finishing a volume of homework that would do justice to Prof. Charles W. Kingsfield in The Paper Chase. That homework, of course, included thousands of pages of legal briefs, from the plaintiff-respondents, the defendant-petitioners, and from too many “friends of the court” to count. So no one can say that the Supreme Court could not prepare adequately for this lesson.

And prepare they must have. Anyone who watches the Supreme Court knows that litigants win or lose on the briefings, and not on oral argument. Still, the Court scheduled three days of oral argument, two of which took up an entire Court day. And as those days approached, they read.

The first day of argument (Department of Health and Human Services et al. v. Florida ex rel. Bondi et al., Docket No. 11-398) showed painfully that the government’s lawyers did not prepare as well as the Supreme Court had. Justice Stephen Breyer made the most famous showing:

Congress has nowhere used the word “tax.” What it says, is “penalty.” Moreover, this is not in the Internal Revenue Code, “but for purposes of collection.” And so why. Is. This. A. Tax?

The problem: if the penalty for not buying health insurance were a tax, then under the Anti-Injunction Act, the case would not be legally ripe until someone had to pay it. The government lawyer tried to argue that a citizen would pay the penalty the same way he paid a tax. But Breyer was having none of that. And if a member of the liberal wing could not accept that, then no one would.

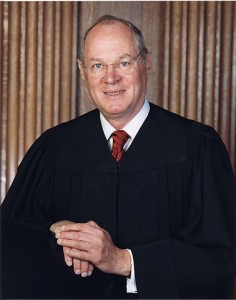

Justice Antonin Scalia, United States Supreme Court. Photo: Steve Petteway, chief photographer (cropped)

The second day of argument became, as one reporter called it, a “train wreck” for the government. “These people are not stupid!” thundered Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia at one point. Scalia went on to state the obvious: if the government wanted to give young people an incentive to get health-care insurance while the getting was good, then they could dispense with forcing insurers to write new policies without regard to pre-existing conditions.

You could solve that problem by simply not requiring the insurance company to sell it to somebody who has a — a condition that is going to require medical treatment, or at least not – not require them to sell it to him at a rate that he sells it to healthy people. But you don’t want to do that.

Ready.

Aim.

Bull’s-eye!

And typical of Antonin Scalia, whose “Nino-grams” are already a Supreme Court legend. That Solicitor General Donald Varilli would not be ready for that is beyond the comprehension of every Court observer.

That, of course, anyone should have expected. What observers did not expect happened when Justice Anthony Kennedy questioned Varilli. Kennedy said that the government proposed to throw out centuries of common tort law and, for the first time, force a citizen to act affirmatively. In most torts, the tortfeasor does something wrong. The “individual responsibility mandate” now calls it a tort if someone fails to do something “right.” That, said Kennedy, would “change the relationship between the government and the individual in a fundamental way.”

The third day of argument technically involved a different case (National Federation of Independent Business et al. v. Kathleen Sebelius, individually and in her capacity as Secretary of Health and Human Services, et al., Docket No. 11-393). At issue this morning: whether the Supreme Court could sever the mandate from the rest of the bill, though the bill has no such clause, and whether the new law breaks the Tenth Amendment in its treatment of the States.

The liberal wing of the Supreme Court, especially Justices Sonia Sotomayor, Elena Kagan, and Ruth Bader Ginsberg, tried desperately to get Varilli to give them good reason not to throw out the entire health care reform bill. More to the point, Justice Scalia warned that removing the mandate, while leaving intact many other things that the bill forces insurers to do (write policies without regard to pre-existing illnesses; carry young adults on their parents’ policies until they are 26 years old, etc.) “would bankrupt the insurance companies.” Barack H. Obama’s allies might accept that, but at least some on the Supreme Court are not ready to.

But Chief Justice John Roberts warned that the States might have brought some of their troubles on themselves:

Isn’t that a consequence of how willing they have been since the New Deal to take the Federal government’s money? And it seems to me that they have compromised their status as independent sovereigns because they are so dependent on what the Federal government has done, they should not be surprised [that the federal government exercises control over them. The states ]tied the strings, they shouldn’t be surprised if the Federal government isn’t going to start pulling them.

The final exam

The arguments are now over. Now comes the final exam.

The lessons were very clear on the salient points of the health care reform bill. Forcing a person to do a thing, good or bad, is not “regulating commerce among the several States” within the meaning of Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution. And ordering a State to set up exchanges, councils, and other things that the law tells them to do, presumes to tell a State what laws it shall make. That directly breaks the Tenth Amendment to the Constitution.

Justice Elena Kagan showed again why she does not belong on the Supreme Court, and certainly should never have heard these cases. She openly advocated for the law, not on Constitutional merits, but on the merits of what the government (and she, when she was part of it) wanted to do for people. In fact, she broke federal law by even sitting there. Title 28 USC section 455 clearly says:

Any Justice…of the United States…shall disqualify himself…where he has served in governmental employment and in such capacity participated as counsel, adviser or material witness concerning the proceeding or expressed an opinion concerning the merits of the particular case in controversy.

Which Elena Kagan did, as Solicitor General while Congress worked on the health care reform bill. But Chief Justice Roberts never took up that question.

Many observers, both conventional and alternative, seem to believe that the Supreme Court, with Justice Kennedy writing for the majority, will strike down not merely the individual mandate but all the bill. But they will do so, not because the bill breaks the Constitution in many ways in addition to the mandate. Instead, they might do so only because the law cannot work without it, and Congress must start all over again.

But the tone of questions at oral argument is no predictor of how the Supreme Court will decide a case. Furthermore, the Supreme Court could have accpeted for review the only case that anyone ever filed, that listed all the ways that this law breaks the Constitution. That case, as regular readers of CNAV will recognize, is Purpura et al. v. Sebelius et al., Docket No. 11-7275. The Purpura case challenged the law on both the grounds that the Supreme Court heard over the past three days and on thirteen other grounds besides. (Nicholas Purpura, the lead plaintiff in that case, told CNAV today that he and Laster might encourage other plaintiffs to file separate lawsuits on each of those other grounds, beginning with the law having originated in the Senate, not the House.)

And so these two cases test the Supreme Court as well as the health care reform law. Will the Supreme Court support and defend the Constitution, as each Justice swore an oath to do? Or will the Court help two other branches of government save face at the expense of the Constitution, and of those Americans whose liberties the Constitution exists to protect?

Related:

A Court without shame, Parts One and Two

Visit msnbc.com for breaking news, world news, and news about the economy

[amazon_carousel widget_type=”ASINList” width=”500″ height=”250″ title=”” market_place=”US” shuffle_products=”True” show_border=”False” asin=”B00375LOEG, 0451947673, 0800733940, 0062073303, 1595230734, 1936218003, 0981559662, 1935071874, 1932172378″ /]

Terry A. Hurlbut has been a student of politics, philosophy, and science for more than 35 years. He is a graduate of Yale College and has served as a physician-level laboratory administrator in a 250-bed community hospital. He also is a serious student of the Bible, is conversant in its two primary original languages, and has followed the creation-science movement closely since 1993.

-

Civilization3 days ago

Civilization3 days agoWhy Europe Shouldn’t Be Upset at Trump’s Venezuelan Actions

-

Executive4 days ago

Executive4 days agoHow Relaxed COVID-Era Rules Fueled Minnesota’s Biggest Scam

-

Christianity Today3 days ago

Christianity Today3 days agoSurprising Revival: Gen Z Men & Highly Educated Lead Return to Religion

-

Civilization4 days ago

Civilization4 days agoThe End of Purple States and Competitive Districts

-

Executive4 days ago

Executive4 days agoWaste of the Day: Can You Hear Me Now?

-

Executive5 days ago

Executive5 days agoWaste of the Day: States Spent Welfare in “Crazy Ways”

-

Civilization2 days ago

Civilization2 days agoDeporting Censorship: US Targets UK Government Ally Over Free Speech

-

Executive2 days ago

Executive2 days agoWaste of the Day: Wire Fraud, Conflicts of Interest in Connecticut

Terry – I agree that the mandate will (and should) be invalidated. But a point of clarification: The government did not argue that the Anti-Injunction Act prohibits SCOTUS from taking up the case until 2014. The government DID advance this argument at lower levels, but the administration eventually abandoned it because the decision was made that it would be best not to delay adjudication of the substantive issues. So the attorney who advanced the Anti-Injunction Act argument on Day 1 wasn’t a “government lawyer.” He’s a private attorney who works in Washington, D.C. and has previously appeared before the Court. When the Court decides that it wants to address a potential argument that neither party to the case advances, it will oftentimes appoint an outside advocate and instruct him to advance the argument. That’s what happened here.

And the Court chewed him up and spat him out.