Constitution

Birthright: cite the case

Donald Trump’s immigration plan still dominates the news cycle, more than twenty-four hours later. Yesterday, Judge Andrew P. Napolitano asserted, but did not prove, the Fourteenth Amendment guarantees an absolute birthright of citizenship to any person born on American soil, under any circumstances. Last night, Bill O’Reilly asserted the same thing. (Bill O’Reilly really should leave that to his “Is It Legal?” team.) This morning, former Governor Jim Gilmore (R-Va.) said the same.

Cite the case, Jim. Cite the case, Bill. Cite the case, Your Honor. (Judge Napolitano surprises us at CNAV. Of all the three, he should have known better than to throw down a legal challenge and fail to cite the case.)

To repeat: do you really think the Constitution gives an absolute citizenship birthright per jus soli (Law of the Soil)? Cite the case!

What the Constitution really says about birthright citizenship

All three cite the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution. So: let us examine that more closely.

All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.

As CNAV said yesterday: the citizenship birthright has a qualifier. Note the phrase: subject to the jurisdiction of the United States. Every civics student learned, at least in the early Seventies, that two classes of children would never get birthright citizenship. Specifically, the children of:

- Foreign diplomats, their staffs, and others who register as foreign agents, or

- Invading enemy soldiers occupying the territory of the United States with a view to hostile possession,

do not get the birthright.

Beyond that, Congress decides “the jurisdiction of the United States,” per Article III, Section 2 of the Constitution:

In all Cases affecting Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls, and those in which a State shall be Party, the supreme Court shall have original Jurisdiction. In all the other Cases before mentioned, the supreme Court shall have appellate Jurisdiction, both as to Law and Fact, with such Exceptions, and under such Regulations as the Congress shall make.

Donald Trump correctly told Bill O’Reilly: no case involving a child born in wedlock, neither of whose parents is even a lawful resident, nor a child born out-of-wedlock, the mother of whom is not a lawful resident, has ever come to the federal courts for a decision. Trump proposes to revoke birthright citizenship. Maybe he intends to re-introduce, or draft a law similar to, Nathan Deal’s Citizenship Reform Act of 2005 (HR 698 in the 109th Congress). After that, he says, let someone test that in court.

Bill O’Reilly certainly ought to cite the case now. Why won’t he? Not that the case would be “dispositive,” as lawyers say. But he could have cited this case:

The most common “birthright citizenship” case

United States v. Wong Kim Ark. The Supreme Court decided this case on 28 March 1898.

Wong Kim Ark, in a photo on a 1931 U.S. immigration document held at the Pacific Region office of the U.S. National Archives and Records Administration in San Bruno, California.

Wong Kim Ark was born in 1873, in San Francisco, California. His parents came to the United States to help build the transcontinental railroad. They never naturalized. But they did reside lawfully in San Francisco.

In 1890, Mr. Wong made a temporary trip to China to see some relatives. In August of 1895 he arrived back in San Francisco, on the S. S. Coptic. The Collector of Customs for San Francisco refused him permission to disembark, on the grounds that Mr. Wong was not a citizen of the United States. The customs collector ordered the steamship officers to confine Mr. Wong on board with the view to having the ship take him back the way he came.

[ezadsense midpost]

Wong Kim Ark immediately filed for a writ of habeas corpus. The United States Attorney for the Southern District of California argued against the writ. At issue: the Chinese Exclusion Acts, by which Congress sought to exclude all Chinese.

The Court named the real issue of this case:

The question presented by the record is whether a child born in the United States, of parents of Chinese descent, who at the time of his birth are subjects of the emperor of China, but have a permanent domicile and residence in the United States, and are there carrying on business, and are not employed in any diplomatic or official capacity under the emperor of China, becomes at the time of his birth a citizen of the United States, by virtue of the first clause of the fourteenth amendment of the constitution.

Note carefully: Mr. Wong’s parents:

- Had a permanent and lawful domicile in the United States,

- Had jobs here, and

- Were not working for the Chinese ambassador, consul-general, or any other such officer.

The court then held specifically that the children of the two classes of parents mentioned already (foreign diplomatic agents and other personnel, and invading troops) would not have the birthright.

The only way to use the Wong case to grant the birthright to an illegal alien child is to construe the distinctions of Mr. Wong’s parents as mere obiter dicta. When that case came before the court, no one even alleged the Wongs came to, or lived in, this country illegally. Nor did the court go so far as to strike down any law excluding any classes of non-citizen from landing or crossing. Nor did the court explicitly say that any person born in the United States, to parents “just passing through,” and left the country with its parents, would be a citizen. Wong Kim Ark did none of these things. He made his temporary visit at the age of seventeen.

So why not cite the case?

Where do the judge, the TV host, and the Presidential candidate stand now? If U.S. v. Wong Kim Ark did grant this absolute birthright they champion, why did they not cite the case? Perhaps because they knew, as Donald Trump said, no one has yet tested the proposition.

In fact, no one has tested any claim to citizenship from a person, born aboard an airliner en route, say, from Toronto to Mexico City, while said aircraft was in American airspace. Nor have we yet seen a test of birth tourism. A pregnant, foreign woman takes a room in a hotel in the United States, and when the time comes for her delivery, she then checks into a local hospital. Does her child get the citizenship birthright?

The Wong case won’t help here. Wong Kim Ark’s parents did not live in any hotel. They came lawfully and had permanent living quarters.

So CNAV asks again: cite the case. If any case specifically says the child has a birthright of citizenship even if the parents (or unwed mother) came into the country illegally, cite the case.

[ezadsense leadout]

Terry A. Hurlbut has been a student of politics, philosophy, and science for more than 35 years. He is a graduate of Yale College and has served as a physician-level laboratory administrator in a 250-bed community hospital. He also is a serious student of the Bible, is conversant in its two primary original languages, and has followed the creation-science movement closely since 1993.

-

Civilization3 days ago

Civilization3 days agoVirginia redistricting – the forgotten theater

-

Civilization4 days ago

Civilization4 days agoWhat the Political Attacks on Fetterman Reveal

-

Civilization5 days ago

Civilization5 days agoTrump’s SOTU Speech a Win, But It’s Not Enough

-

Clergy4 days ago

Clergy4 days agoDecapitating Amalek: Iran, Purim, and the Obligation to Act in Time

-

Education5 hours ago

Education5 hours agoWaste of the Day: Boston’s Soccer Stadium Cost Almost Tripled

-

Civilization3 days ago

Civilization3 days agoIran: A Humbling Reminder of the Public Square We Take for Granted

-

Executive2 days ago

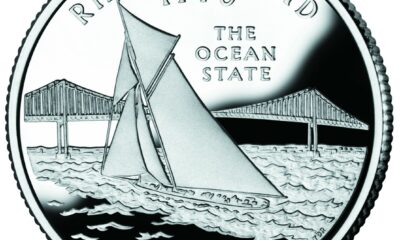

Executive2 days agoWaste of the Day: Rhode Island Overtime Payments Approach $300,000

-

Civilization5 days ago

Civilization5 days agoTop Library Advocate: Backing Drag Queen Story Hour Supports Parental Choice

The Supreme Court failed to make an exception for illegal Chinese immigrants in the decision, so it follows that they are covered under it. Illegal Chinese immigration was a concept at the time, due to the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act under President Arthur in 1882. The Court either intended for children born of illegal aliens to be included in this decision, or made a grievous oversight in excluding the children of foreign soldiers and diplomats but somehow forgetting to name the third group as outside the decision.

The Court could not have included the children of illegal Chinese immigrants in that decision, because that is not what Wong Kim Ark was, and that is not what his parents had been. Not unless you are trying to allege an ex post facto law. Which is unconstitutional per Article I Section 9.

So if the Court was only concerned with Mr. Wong Kim’s specific case, why did they ever mention the other two exceptions?

At the time, those were the only two exceptions of which they could conceive. Nobody ever conceived of millions of people slipping into the country without a visa. In those days, such things didn’t happen.

As I said above:

Chinese Exclusion Act- signed into law by President Arthur on May 6, 1882.

Illegal Chinese immigration was most certainly a thing by that point, as evidenced by the creation of INS in 1900: link to archives.gov

Even though this was after the case in question, it demonstrates that illegal immigration from China was certainly an issue at the time under the Act, and would have been on the minds of the Supreme Court Justices as they crafted their decision.

The Wongs settled in this country earlier than 1882. No President Arthur, no Chinese Exclusion Acts in 1873. Wong Kim Ark was born under the old law. Under the Constitution, no law, criminalizing any particular behavior, can apply to acts done before its enactment. That would be an ex post facto law. (Actually, Wong could have sued to strike down those same Chinese Exclusion Acts as the unconstitutional bills of attainder they were.)

You’re missing my point. The Court clearly intended their case to set a precedent since they listed exceptions to their ruling that didn’t apply to that particular case. Mr. Wong Kim Ark’s family had no connection to the diplomatic staff, and were not members of an invading army, yet the Court mentioned them in their decision. Why? Because they knew their case was going to be cited in further cases regarding citizenship, and didn’t want it to be used to justify citizenship in either of those cases. They did not, however, exclude children of illegal immigrants from their ruling. Therefore, either the Court simply forgot to include them (highly unlikely bordering on impossible) or it intended the ruling to apply to them as well.

In summary, the Court mentioned two exceptions that did not apply to the case at hand, yet pointedly did not add a third for illegal immigrants.

I don’t have to concede that point. The only way those Chinese were even getting in was off a boat. That made them easy to intercept. The spectacle of thousands of them walking across a largely unsecured border didn’t start to happen until the twentieth century.

Nicks N Raygun liked this on Facebook.

For some reason it has become commonly accepted that the 14th Amendment to the Constitution makes it mandatory that anyone born in the United States is automatically entitled to US citizenship. We often see those ignorant allegations being pompously announced by ignorant media talking heads and equally ignorant politicians as absolute facts. The legal facts are quite different from their false assertions and the fact is that the Constitution’s 14th Amendment actually exclude certain individuals from this automatic citizenship. This includes the children of illegal immigrants or so-called “anchor babies”.

Lets just go over the history of the 14th Amendment. It was passed and ratified on July 9, 1868 after the end of the civil war and the part of the Amendment concerning automatic citizenship was specifically intended to keep states from disenfranchising blacks born in the United States from citizenship. The exact language on that part is as follows. “All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.”

Those who are ignorant of the law, which apparently is most of the US population, often claim this gives blanket citizenship to all those born in the United States. However, words mean something particularly when it comes to the law and they ignore the phrase “and subject to the jurisdiction thereof”.

In 1866 while this amendment was in the process of being passed Senator Jacob Howard clearly spelled out the intent of the 14th Amendment by stating: “Every person born within the limits of the United States, and subject to their jurisdiction, is by virtue of natural law and national law a citizen of the United States. This will not, of course, include persons born in the United States who are foreigners, aliens, who belong to the families of ambassadors or foreign ministers accredited to the Government of the United States, but will include every other class of persons. It settles the great question of citizenship and removes all doubt as to what persons are or are not citizens of the United States. This has long been a great desideratum in the jurisprudence and legislation of this country.”

This understanding was reaffirmed by Senator [Edward Cowan when he stated “A foreigner in the United States] has a right to the protection of the laws; but he is not a citizen in the ordinary acceptance of the word…”

The phrase “subject to the jurisdiction thereof” was intended to exclude American-born persons from automatic citizenship whose allegiance to the United States was not complete. With illegal aliens who are unlawfully in the United States, their native country has a claim of allegiance on the child. Thus, the completeness of their allegiance to the United States is impaired, which therefore precludes automatic citizenship. That is pretty clear and it is a mystery to me why everyone does not understand it.

by Bruce Davis View Blog

Ann Coulter visited this issue in her weekly column. For everyone’s information, she denounces the Wong case as one of the Court’s most egregious errors. In fact, she calls it “elementary.”

Sorry the link did not come through;

link to teapartynation.com

But illegal Chinese immigration was clearly enough of a problem to warrant the creation of INS in 1900, so while it was certainly not as significant an issue as our modern border crisis, it was still something that the Court would have addressed if they intended to.

1900. That’s two years into the future of the decision, and five years after they wouldn’t let Wong Kim Ark off the boat, and he filed his original petition for a writ of habeas corpus.

That doesn’t mean illegal Chinese immigration wasn’t an issue before 1900. This information: link to archives.gov from the National Archives lists cases concerning deportation of illegal immigrants from several states. While some of the records only go back to 1900 or later, some, including Arizona and Texas, date back to the 1890’s, before the decision was rendered.

Nevertheless, Wong Kim Ark’s parents were perfectly lawful residents. Such were the facts before the court.

That they were legal residents is not in question. But the Court clearly intended for their decision to apply to cases outside the particular ramifications of that one. Wong Kim’s parents were also not members of an invading army or diplomatic staff, but the Court still mentioned those two cases as exceptions. In citing two places where their ruling would not apply, the Court indicated that it intended its ruling to apply to other areas outside the case.

We can repeat back-and-forth until Doomsday. But you will never convince me to accede to the wholesale theft of my hard-earned substance to feed yet more welfare clients swarming in from across the border, and using anchor babies to gain eligibility for same.

[…] he see our article yesterday calling on him, former Governor Jim Gilmore (R-Va.), and Judge Andrew P. Napolitano to […]

Whether you accept it or not is irrelevant. I’m not asking you to embrace anchor babies as a good thing or something we should encourage, I’m trying to defend the position that under the Wong Kim v. United States decision, children of illegal immigrants are citizens by birth. I’m not asking you to accede to anything, merely to acknowledge that the Supreme Court’s decision (however incorrect you may believe it to be) allows children of illegal immigrants to be citizens by birth.

And I say you are in error. The Wong case did not treat that issue, since the Wongs were all lawful residents. Anything else is obiter dicta.

As you said in your column: “The only way to use the Wong case to grant the birthright to an illegal alien child is to construe the distinctions of Mr. Wong’s parents as mere obiter dicta.” So are the distinctions so listed obiter dicta, or not? If they are, then the Court did not rule on a child in the specific parental circumstances listed, and therefore left the ruling open to apply to any child born in the United States. If they are not, then the Court made two critical exceptions: “not employed in any diplomatic or official capacity under the Emperor of China,” that is, a diplomat or members of an army, but left out a third: “illegally residing in the nation.”

The other distinctions the Court made: “hav[ing] a permanent domicile and residence in the United States, and [being] there carrying on business,” are easily met even by an illegal immigrant.

The Court put those in to strengthen the case for letting Mr. Wong get off the boat and stay in this country. That makes them essential to the argument and conclusion of the case at hand. Obiter dicta, by definition, are non-essential observations. Those set no precedent.

And the enumeration, in an opinion, of certain classes should not construe as to deny the relevance of other classes of people not contemplated at the time, if such classes come to exist in future.

So the Court believed that his parents being 1) not employed as diplomats, 2) not members of an invading army, 3) having a permanent residence, and 4) being engaged in business in the U.S. was relevant to the case, but not the legal status of his parents?

If we were to look at the decision, then, it applies to a child who was born in the United States, whose parents are not diplomats or members of a foreign military, who have a permanent residence, and are engaging in business. What part of those criterion does a child of illegal immigrants born here fail to meet?

You left out the status of the parents as having a lawful domicile that, to all appearances, constituted permanent residence. All these things bore on the court’s reasoning in Wong. And even so, the Wong court made a reversible error, as Ann Coulter points out. (Apparently she sourced this from the Yale Law Journal.) The 1898 court referred to English common law, and more than that, to feudal law. Under that, a sovereign or peer (duke, marquess, earl/count, viscount, or baron) counted as his subjects all persons born on his land. But the proper foundation of American common law is Roman law. And under that, citizenship is a privilege, and the only sure birthright belongs to the children of citizens. In other words, jus sanguinis – the Law of the Blood.

I did not leave it out, see 3) in my response above. The Court did not specify a _lawful_ residence, which of course an illegal immigrant cannot technically have: “but have a permanent domicile and residence in the United States.” Illegal immigrants can most certainly have a permanent domicile, and many do.

If the Court made an error, then that error can only be overturned by a later Court ruling or an amendment to the Constitution, neither of which have occurred.

As far as the foundations of U.S. Law are concerned, Professor Lawrence Friedman of Stanford University demonstrates that American law has many roots in English Common Law. The United States took as much if not more of its legal tradition from England than from Rome, and has departed from both over time. Examples regarding citizenship: we allow women to vote, Roman Law did not; we allow former slaves to vote, Roman Law did not; we allow non-citizens to have the right to a legal trial, we allow citizens to be executed, we allow non-citizens to hold property, etc.

The court specified a permanent residence. A residence has to be lawful or it can’t be permanent.

Permanent- Fixed, enduring, abiding, not subject to change. Generally opposed in law to “temporary.” (Black’s Law Dictionary) link to thelawdictionary.org

Permanent does not require legality.

It did in this case. Read the opinion again. The article has a link.

[…] during the next several years, we will all be told that the Wong Kim Ark Supreme Court case changed everything in that Wong Kim Ark was allowed to stay and receive citizenship because he was born here even […]

[…] when CNAV has an anti-bot firewall in place.) For the benefit of those who didn’t see them, here they are. (See also Dwight Kehoe’s treatment of the Fourteenth Amendment.) But CNAV notes other […]