World news

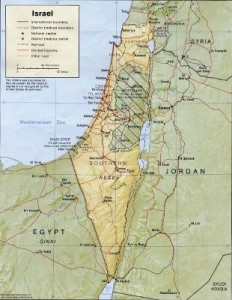

Israel: an embarrassing state

A propos of Israel’s Independence Day, allow me to repeat what I occasionally say: given its inept and dysfunctional political institutions, Israel’s continued existence is the political proof of God’s existence. Let’s probe this subject from an unconventional perspective.

People usually blame factions, not structures

If you are a citizen or even a political analyst living in a country afflicted by some serious and recurring problems, you are more likely to blame the ruling party than the political structure of the regime. It’s much easier to denounce the failings of your prime minister or his party.

It’s also more “practical” because it’s far more difficult to change the character of the regime than to elect a new prime minister or to replace the party in power with its competitor.

Few people in a democracy discern or trouble themselves analyze the defects of their political institutions. Fewer still see the relationship between faulty government policies and their country’s electoral laws. Most people take their political institutions and electoral laws for granted. And well they might, else political instability and even revolution might result.

Nevertheless, many public problems are the consequence of unrecognized flaws in a country’s political institutions. The attributes of these institutions, such as (a) the qualifications for voting and holding office, (b) the mode of election, (c) the size, tenure, and powers of the various branches – these attributes can either increase or decrease the probability of getting competent office-holders as well as the political continuity required to pursue coherent public policies.

Israel, change your election laws!

I have elsewhere shown that Israel’s political institutions are poorly designed, that they make it extremely difficult to pursue policies conducive to national solidarity, self-confidence, and security. Although more and more people in Israel are learning this, basic institutional or structural change is very difficult, and for various reasons.

First, as previously indicated, most people find it simpler to blame the failings of this or that politician or party for their country’s plight, rather than the design of their political institutions.

Second, there are vested interests in Israel, especially political parties, which want to preserve the existing political system and electoral laws.

Third, Israel’s precarious situation in the Middle East discourages basic institutional reform.

Fourth, there are many people who do not see that it’s precisely the defects of Israel’s political institutions that are largely responsible for their nation’s external dangers.

For example, it’s easier to say that the government is inept, or that it ignores public opinion, than to see that the country’s political institutions may actually discourage highly qualified people from seeking public office on the one hand, while making it easier for low caliber politicians to betray their voters on the other.

Very few people in a democracy have the professional knowledge to recognize that electoral laws may be largely responsible for inferior leadership and even official corruption. But electoral laws very much determine not only the extent to which a government is democratic and faithful to the electorate, but also whether those laws are conducive to advancing to public office men capable of dealing effectively with the country’s serious problems.

Does Israel’s government represent the people?

Consider. Democracy means the rule of the people, which translates into the rule of the majority. The rule of the majority means the opinion of the majority on this or that public issue. Knowing a pronounced majority-held opinion, the Knesset has an obligation to translate that opinion into public law; or, in the case of the Executive, to apply existing law in conformity with that public opinion. Although this is a rather simplified view of things, it corresponds to the idea of representative government.

Admittedly, public opinion on a particular issue is not necessarily correct or just. But there are occasions when public opinion actually represents the basic principles of any civilized society.

Here is an example. On May 31, 1994, more than eight months after the signing of the Israel-PLO Agreement, the following question was posed to Hebrew-speaking Israelis in a Gallup poll:

There are those who claim that senior PLO-Palestinian officials suspected of complicity in the murder of Israelis, should not be put on trial, because such an action would probably damage the peace process. There are others who claim that everyone is equal before the law, and therefore PLO officials suspected of illegal acts should be investigated and put on trial. Which claim do you support?

Almost 66% of the population – including 59% of Labor voters – held that senior PLO officials, if complicit in the murdering of Jews, should be put on trial even though it might damage the peace process!

From this data alone, it should be evident that hardly any government of Israel truly represents the public’s attitude on that issue, hence on the policy of “territory for peace.” Even if many Israelis are resigned to that policy, it does not accord with their deepest and abiding convictions. They are simply following their “leaders,” none of whom possess the wisdom and courage to offer a viable alternative. So much should be obvious.

But it should also be obvious that if Israel’s political institutions and electoral laws were designed in such a way as to make Israeli politicians more respectful of, and more dependent on, public opinion, the September 13, 1993 Israel-PLO Agreement would never have taken place!

If MKs were dependent not on their parties but on the voters for their continuance in office, Oslo would not have become a household term! The truth is that Israel’s government can ignore, and has ignored, public opinion on issues concerning the borders of the state, which implicates Oslo.

This fact places in question the universal belief that Israel is an authentic democracy – however democratic it may appear compared to its Arab neighbors. But to transform Israel into genuine democracy would require fundamental changes in its political institutions and electoral laws. Merely to raise the electoral threshold by one percent, or replace one Prime Minister or party with another, will not solve Israel’s basic problems, as we have seen with two decades of Oslo and thousands of Israeli casualties.

But there are also the vested interests of journalists and political scientists who are reluctant, at this late date, to call the public’s attention to the inherent flaws of Israel’s structure of government for which the founders of the state are responsible. That might embarrass these political analysts, to say nothing of the flawed statecraft of the founders!☼

-

Civilization3 days ago

Civilization3 days agoWhy Europe Shouldn’t Be Upset at Trump’s Venezuelan Actions

-

Executive4 days ago

Executive4 days agoHow Relaxed COVID-Era Rules Fueled Minnesota’s Biggest Scam

-

Christianity Today3 days ago

Christianity Today3 days agoSurprising Revival: Gen Z Men & Highly Educated Lead Return to Religion

-

Civilization4 days ago

Civilization4 days agoThe End of Purple States and Competitive Districts

-

Executive4 days ago

Executive4 days agoWaste of the Day: Can You Hear Me Now?

-

Executive5 days ago

Executive5 days agoWaste of the Day: States Spent Welfare in “Crazy Ways”

-

Civilization1 day ago

Civilization1 day agoWhy Europe’s Institutional Status Quo is Now a Security Risk

-

Civilization2 days ago

Civilization2 days agoDeporting Censorship: US Targets UK Government Ally Over Free Speech

Si Lent Cal liked this on Facebook.