Reviews

Obedience – biggest challenge to liberty

Obedience. Director: Stanley Milgram, Ph.D. With Stanley Milgram, John T. Williams, James J. McDonough, and many others who prefer to remain anonymous. University of Pennsylvania Films in the Behavioral Sciences, 1962.

The Tenth Level. Director: Charles S. Dubin. With William Shatner, Lynn Carlin, Ossie Davis, Viveca Lindfors, Estelle Parsons, Roy Poole, Mike Kellin, Richard McKenzie, et al. CBS Productions, 1976.

Joe Biden demands obedience – after Stanley Milgram studied it very closely

President Joe Biden has plunged the United States into a turmoil only the protests in Australia can rival. He did so by ordering the Occupational Safety and Health Administration to draw up a vaccine mandate for private employers. As CNAV contributor Darrell L. Castle pointed out the following week, when he did that he started a war with dissidents.

And sadly, a good part of the country has enlisted in Biden’s War, on his side. This ought to surprise no one. Who would have thought that anyone calling himself an American would push obedience so hard as to join the tyrants? Stanley Milgram, that’s who. Back in 1962 he shared his findings with the world. Fourteen years later, CBS’ Entertainment division delivered a fictionalized account of the Milgram Obedience Experiment – and its likely aftermath. To his discredit, Stanley Milgram never followed up with any of his subjects. To their credit, CBS made a telling – and brutal – suggestion of how lucky Milgram was to escape prosecution and censure. But as tragic and ugly as the Milgram Obedience Experiment was, Milgram made a salient point. To quote him: we cannot rely on human nature to stand in the way of tyranny. The SARS-CoV-2 experience has, sadly, proved that.

Who was Stanley Milgram?

The details of the life of Stanley Milgram come from Wikipedia. He was born in 1933, in New York’s Bronx. The Holocaust affected his family directly, in that some survivors stayed in the Milgram home. Milgram acknowledged the plight of European Jews in his Bar Mitzvah speech.

As horrifying as the Holocaust was, and as much as that horror struck home with him, the trial of Adolf Eichmann struck him harder. Where, he asked himself, does a man like Eichmann come from? More to the point: what makes a man like Eichmann follow another man like Hitler? And: what makes ordinary citizens follow the Eichmanns and Hitlers?

So in 1962 he decided to test this. That test did indeed come at great cost to his professional career. But no one can deny the lessons of his Obedience Experiment.

How the Milgram Obedience Experiment ran

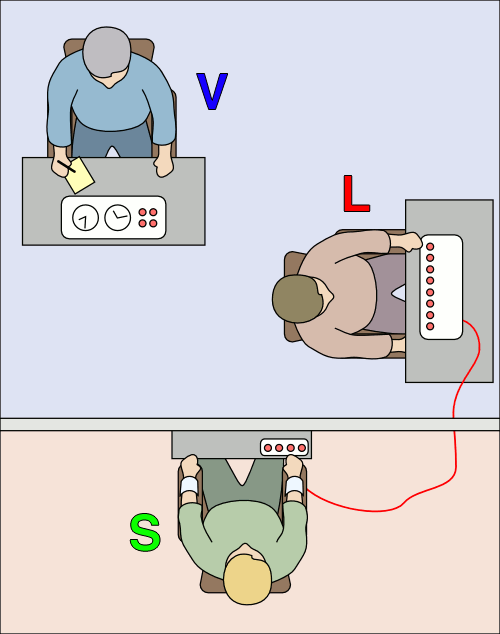

The documentary Obedience runs 44 minutes, and in it Milgram tells us, in dry “research-ese,” how he ran his experiment. In the accompanying image, Learner “S” sits in a chair, under restraint. Teacher “L” reads to him a list of fifty word pairs, beginning with “Blue girl”, “nice day,” etc. L also sits at a console with a row of numbered spring-loaded levers, each with a voltage rating. His job: quiz S on the word pairs after reading them through only once. If S answers correctly, move on. If S answers wrong, deliver a shock from the shock console. Move up the voltage scale with each mistake S makes. And if L reaches the highest voltage, keep delivering a shock at that level until S gets it right!

Of course S receives no shocks at all. The setup has several variations, but all amount to this: S pretends to take shocks, and starts to protest at some point. He might bang on the wall, or play a tape of him shouting a time-honored protest:

That’s it. Let me out of here. My heart is starting to bother me now. Let me out. Let me out! You can’t keep me here against my will!

And so forth and so on. Oh, this reviewer forgot to mention. L watches Experimenter “V” strap S into his chair, and listens to S say he’s already had a bad EKG.

V: the coach

V sits at a table with two stop clocks. One notes how long L waits before giving the shock; the other notes how long each shock lasts. V also knows how far up the row L has moved. But V’s most important job is to coach, or nudge, L to continue the lessons – and the punishments.

The experiment requires that you continue. We told you that the shocks, while painful, are not dangerous. Whether the learner likes it or not, the experiment must continue. It is essential. You have no choice.

And sometimes L would balk. But half the time…L did not balk.

Your reviewer took Psychology 101 at Yale in the fall of 1977. As part of that, your reviewer took part in psychological experiments. And one thing to which your reviewer can attest is that investigators in psychological experiments always lie to their subjects. Which is why L does not know that S is not getting any shocks and is in fact an accomplice. Every psychological experiment is a big practical joke on the subject. The idea is to see how the subject will react. In this case, Milgram sought to learn how far each subject would “go” before balking. (Only in this case, the joke wasn’t funny. The American Psychological Association held up his application to join that body. And he never, ever, got tenure at Harvard University, where he presented and defended his doctoral dissertation.)

Variations on the theme

As your reviewer mentioned, Dr. Milgram made variations on the theme. He used fifty subjects with each trial, varying in education from grade-school dropouts to men with advanced degrees. (In Obedience Milgram does not mention ever having a woman subject. But the CBS Tenth Level movie has the stand-in for Milgram testing women subjects.)

The setup between S, L, and V varried as follows:

S could be out of the room, and able to communicate only by banging the wall. Or he might play the “Let me out of here” tape. Or: S could be in the same room with L. And in one setup, L would have to push S’s hand on a shock plate with every shock he dealt!

V could be in the same room with L, or out of the room giving his coaching by telephone.

Obedience always slacked off whenever V was out of the room, or S was in the room. It slacked off even further when L had to hold S’s hand down on a shock plate. In fact, obedience slacked off when S could protest on tape instead of merely banging the wall.

Awesome Yale v. dingy back-street office: no difference

Milgram even tested the outside setting of his experiment. When you bring an ordinary Townie into a place like Yale, he might regard it with respect, even awe.1 So Milgram ran the Obedience Experiment in a run-down rental office in downtown Bridgeport, a neighboring city to New Haven. And he got statistically similar results! The setting did not matter, though the setup certainly did.

Milgrim describes one more variation on the theme. In it, L would be part of a group. Sometimes he would still be the one to give the shocks; at other times he would be just another member. And sometimes the group’s other members would balk; at other times they would “egg him on.” And yes, the members were all actors, producing an artificial group dynamic. The subjects most often followed the group dynamic.

Which now brings us to the fictionalized drama by CBS.

The Tenth Level

The Tenth Level takes its name from the level – ten of twenty-five – that seems to be the floodgate point. When an L subject reaches the Tenth Level, he doesn’t stop.

Filming took place almost certainly at Yale College, though the story uses a fictitious college name. The gothic structure where CBS shot the exteriors looks much like Yale’s Pierson Residential College. (The real psychological laboratory stands on Hillside Avenue, north of Grove Street and between Prospect and Temple Streets. Pierson College is on the western side of the campus and does not have any classrooms or laboratories.)

William Shatner plays Milgram, under a fictious name, of course. Lynn Carlin plays his love interest – well, he’s interested, but she isn’t. (Art anticipating life? The sexual harassment case of Alexander v. Yale would hit the courts two years later.) Roy Poole plays Shatner’s colleague – but Shatner and Poole take turns playing the V role. Charles White gives an excellent performance as S, the victim-accomplice. Ossie Davis, Viveca Lindfors, Estelle Parsons, Richard McKenzie, Mike Kellin, and many others play L subjects.

Obedience leads to a breakdown

Mike Kellin deserves special mention. After he gets to about Level 18, he grabs a hammer and starts smashing the console. Then he bolts from the laboratory before V and S have a chance to “reconcile” him. The young man then goes into a bar, where he provokes a man to beat the daylights out of him by asking him whether he dropped napalm on a village in Viet Nam. And when the Ethics Committee calls him to testify, he says:

I’m grateful to [the Milgram stand-in]. Because now I know that, had I been at My Lai, I would have shot dogs, and cats, and women, and children, and babies!

As Stanley Milgram would be first to tell you, not one of his L subjects ever broke down that way.

As shocking as this is, the other V actor testifies that he had to “do his job as a scientist” to satisfy the chief investigator.

V: I wouldn’t be doing my job as a scientist.

Board chairman: As your subjects were doing their jobs?

The investigator’s regret

In the last scene, Shatner’s character is in his laboratory, after the Ethics Board has censured him. His love interest then forces him to confront the most brutal fact of all. Which is: he himself was obeying a prime directive to develop the scientific findings! This despite the pain he visited upon his subjects and even his staff. The realization that the Obedience Directive affected him, too, and clouded his ethical judgment, makes him break down and cry. (That didn’t happen to Milgram, either.)

Deviations from fact

Obviously The Tenth Level describes the aftermath of the Obedience Experiment far more extensively than the Obedience documentary does. The major liberties Level takes are:

- The L subjects openly sob as they progress to level after level.

- S personalizes his protests, even calling each L by name when saying, “That hurts! Oh, don’t do that a-gainnnnnn!” Etc.

- V stands at the console table, leans over the console, and says, “Next switch, please. Next switch, please.” Etc.

- The shock console numbers the levels consecutively, not by voltage.

- The twenty-fifth and highest level has a special pulsing red light associated with it.

- V “selects” teacher and learner by using a two-headed coin. Milgram’s V initially handed L and S each a slip of paper labeled “Teacher” and had S say, “Learner” on cue.

- V straps S into a chair that looks like a dentist’s or barber’s high chair. This makes the setup the more dramatic.

A preliminary experiment Milgram never ran

But the most interesting variation tells of one experiment Milgram did not document in Obedience. In it, Shatner’s investigator brings in other subjects and teases them with storyboards showing the setup. He asks each of these subjects at what level he would balk. Most of them say they would go no further than Level 4, if they would do it at all. (And in fact, The Tenth Level does depict one L subject balking at Level 4.)

V: The experiment requires that you continue.

L: I don’t care what the experiment requires! You cannot do that to a fellow human being.

But what those preliminary subjects say, and what the L subjects actually do – are two entirely different things.

Obedience and The Tenth Level – the dramatic craft

Stanley Milgram, in making Obedience, sought merely to present his findings. He did not intend to produce a chilling drama. But Obedience does chill the viewer with Milgram’s dry style of delivery. He takes pains to explain that L and S always “reconcile in an atmosphere of friendship” after the session. All this is part of “seeing to the psychological welfare of the subjects.” Well, the APA and the Tenure Committee at Harvard were never 100 percent satisfied with that; hence his career troubles. This film leaves the viewer wondering: how would I react in that scenario? And how embarrassing must it be for each subject to remember what he did?

Easy enough for a subject who balked early, whether because he didn’t want to deliver a shock at 150 volts (the maximum level was 450!), or because S was (as L thought) yelling, “Let me out of here! Let me out!” etc. But what about the L subjects who kept delivering shocks even after S grew deathly quiet and quit answering? Readers will realize, we trust, that S was playing dead. Milgram reported fifty percent obedience in the scenario with S in another room and playing the protest tape. He did not say how high up the scale L would have to get to score positive obedience. But Milgram did show L subjects balking at the eighth switch when S started yelling, “Let me out of here.”

Fact v. fiction

The Tenth Level, by contrast, does play the story for dramatic effect. The storyboard preliminary experiment is a stroke of dramatic genius, besides being an experiment Milgram should have run (or documented if he did run it), but didn’t. It sets the viewer up for the drama of the Obedience Experiment itself.

The Ethics Board hearing – which stands in for the deliberations by the American Psychological Association and the Harvard University Psychology Departmental Tenure Committee, no doubt – brings the full effect on the L subjects into full relief. Of course, Mike Kellin’s performance does that to an even greater degree. His taking the hammer to the shock console is one of the greatest dramatic disasters any screenwriter ever wrote. (Your reviewer uses the word disaster loosely, in that every story needs “three disasters and an ending.”) And yet, no one tries to act “over the top,” as they would, say, in a Joseph L. Mankiewicz movie. This is television, which makes it up close and personal, like a living-room chat.

William Shatner, of course, was fresh off his gig as Captain James T. Kirk in the original Star Trek. Compared to that often ham-handed performance, he delivers a much more nuanced – and effective – performance in Level. Roy Poole does equally well as Shatner’s colleague, confronting his own unpleasant truth before the Ethics Board. Mike Kellin’s performance speaks for itself.

Lessons in obedience for today

Taken together, these two films drive home a point that was, sadly, lost on most people when they came out. Obedience played mostly to academic audiences. Unaccountably, the viewing public almost forgot The Tenth Level completely. But at least two YouTubers have uploaded bootleg transfers of The Tenth Level onto their channels. Another has uploaded The Tenth Level in a multi-part form. How long they will remain on YouTube is anyone’s guess.

That the public forgot these films, bodes ill for the United States of America. For we now see a classic scenario from Obedience, especially the one with the managed group dynamic. People have given up their freedom, and crashed their economy – because someone in a lab coat told them to! Someone should ask William Shatner about that – for after all, he speaks that very line in Level.

And what Stanley Milgram would say of this spectacle, CNAV is almost afraid to ask. Would he throw in with the likes of Fauci et al.? Or would he, Bronx Jew that he was, remind everybody:

Didn’t I tell you?!? Didn’t I illustrate how the Holocaust came about? And why didn’t you listen to me? Especially my fellow Jews. “Never again,” you said. And you let this happen! Gonifs, all of you!

We’ll never know. Milgram died in 1984, having lived to see CBS dramatize his work in Level. (Though Milgram consulted on the project, it did not satisfy him. He didn’t even want screen credit for it.)

See them now, when the lessons are fresh!

Obedience

The Tenth Level

Update

See also Experimenter. Director: Michael Aimereyda. With John Palladino, Anthony Edwards, Jim Gaffigan, Peter Sarsgaard, and Winona Ryder. Magnolia Pictures, 2015. This movie replicates almost exactly the original Milgram setup as his documentary depicts it. Herewith an official trailer.

1 That was true in the Sixties. It was less true when your reviewer attended, and Mayors like Frank X. Logue and Ben DiLieto campaigned on attempting to force Yale to make payments to the city in lieu of the property taxes from which Yale, as an institution of higher learning, was exempt. Indeed, Town-Gown tensions ran at a fever pitch, and only the Great Strike of 1977 interrupted that.

Terry A. Hurlbut has been a student of politics, philosophy, and science for more than 35 years. He is a graduate of Yale College and has served as a physician-level laboratory administrator in a 250-bed community hospital. He also is a serious student of the Bible, is conversant in its two primary original languages, and has followed the creation-science movement closely since 1993.

-

Accountability2 days ago

Accountability2 days agoWaste of the Day: Principal Bought Lobster with School Funds

-

Constitution2 days ago

Constitution2 days agoTrump, Canada, and the Constitutional Problem Beneath the Bridge

-

Executive20 hours ago

Executive20 hours agoHow Relaxed COVID-Era Rules Fueled Minnesota’s Biggest Scam

-

Civilization19 hours ago

Civilization19 hours agoThe End of Purple States and Competitive Districts

-

Civilization4 days ago

Civilization4 days agoThe devil is in the details

-

Executive4 days ago

Executive4 days agoTwo New Books Bash Covid Failures

-

Civilization3 days ago

Civilization3 days agoThe Conundrum of President Donald J. Trump

-

Executive4 days ago

Executive4 days agoThe Israeli Lesson Democrats Ignore at Their Peril

[…] worst enemies he could possibly make in Western society today. Someone might be preparing a Milgram Obedience Shock Generating Apparatus. For real this […]

[…] government is in the “divisive” business and the only “together” they understand is your obedience. Despite your heroic Tweet, obedience is exactly what you gave them when you turned your back on […]

[…] state of affairs reminds me of the Stanley Milgram Obedience Experiment. You can look up the details of the experiment, perhaps, in the annals of your […]

[…] And those same students got onto the faculties of our colleges and universities, with notable exceptions. These “tenured radicals” govern our universities today. Even Yale University, which didn’t blow up then, now has become a full-blown Stanley Milgram Obedience Experiment. […]