Human Interest

Apollo 11: moonwalk

Forty-five years ago, two men (Neil A. Armstrong and Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin) set foot on a different world. It was the greatest moment in the history of exploration, and a moment men had anticipated for nearly a century.

Earlier imaginings of landing on the moon

Two famous European authors imagined a trip to the moon. They were, of course, Jules Verne (From the Earth to the Moon) and Herbert George Wells (First Men in the Moon). Wells’ vision was the more richly detailed: an eccentric scientist develops a substance to cancel the force of gravity. He uses it to build a tiny spacecraft to go to the moon. He and two others find more than another world. They find a civilization. (Ray Harryhausen would add another story to frame this: a multinational crew lands in a modular ship. They find evidence of that first landing, decades earlier. Then they find the civilization. Sadly, it is dead, and all its artifacts crumble into the lunar dust.)

Jules Verne’s vision was darker. An arms merchant develops a dangerous high explosive. He uses it to drive a spacecraft to the moon. A rival scientist commits sabotage. This results in the deaths of all aboard.

Apollo 11 lands

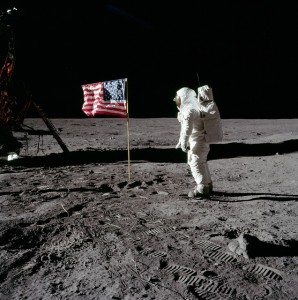

Astronaut Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin stands next to the flat at the Apollo 11 camp. The flag seems to flutter because the astronauts bent its supporting wire out of shape as they planted it. Photo by Astronaut Neil A. Armstrong, courtesy of NASA

This page of NASA’s publication Apollo by the Numbers tells the story of the Apollo 11 moonwalk. After the Eagle (the Apollo 11 Lunar Module) landed, Neil Armstrong changed the call sign to “Tranquility Bases.” By doing this he emphasized that their spacecraft was more than a spacecraft now. It was a camp. For the first time in history, men pitched a camp on another world.

For two hours Neil and “Buzz” checked their craft’s systems. Then they ate their first extraterrestrial “camp” meal. They did not rest. Maybe they were too restless for that.

Six hours after landing, Neil was ready to go out. Actually, Neil and Buzz had disputed who would go out first before they took off. Buzz felt a commander’s place was aboard ship, and he should send his subordinate out. Neil didn’t think that way. To him, setting the first feet on new territory (or “lunatory”) was a command privilege. It took Boss Man Donald K. “Deke” Slayton to settle the matter. (How Slayton got to be Boss of the Astronaut Corps is another story. His buddies gave him that title as a consolation prize after his heart disqualified him from flight. He would not correct that impression until the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project mission, six years later.)

Both men suited up, of course, before they decompressed the LM. (This craft was far too small to carry an airlock.) Neil backed through the hatch, with Buzz to guide him out.

The first thing Neil did was to pull a lever on the top of the landing ladder. Out popped the “Modular Equipment Stowage Assembly,” essentially a fold-out crane holding the first part of the equipment they would use as they finished pitching camp. Part of this equipment was a TV camera. This camera started sending a picture back the instant the crane settled down.

And on home television sets around the world, a picture of two play-actors going through the motions of going out of the LM, gave way to a live shot from the moon.

Neil moved down the ladder, one step at a time.

Eventually he stood on the pan-like landing pad.

Then he put his foot down on the moon, at 0256 hours GMT (now UTC), or 2156 hours Houston (that is, Central Daylight) time.

And he spoke his famous line:

That’s one small step for a man, one…giant leap…for mankind.

Note: he said one small step for a man. But he said it so quickly that later historians forgot he used that little particle.

Not long after that, Neil Armstrong reported the most important findings:

The LM descent engine did not blast a crater.

The lunar surface had six to eight inches of loose dust. Underneath this was hard regolith that stuck together.

They had never had to worry about sinking into the lunar dust. Nor would the crew of any mission after Apollo 11.

Related:

Video:

Short version showing Armstrong descending.

Long version: three hours of footage of Armstrong and Aldrin dancing like gazelles in the one-sixth gravity.

[subscribe2]

Terry A. Hurlbut has been a student of politics, philosophy, and science for more than 35 years. He is a graduate of Yale College and has served as a physician-level laboratory administrator in a 250-bed community hospital. He also is a serious student of the Bible, is conversant in its two primary original languages, and has followed the creation-science movement closely since 1993.

Bill Luck liked this on Facebook.

[…] Apollo 11: moonwalk […]

Apollo 11 was indeed an awe inspiring project… unfortunately, 45 years later, virtually no more progress has been made in man space flight, and it is seeming more and more like the efforts of the those involved had little practical significance. Thus far, it seems as though Neil Armstrong’s famous line was untrue, because the project did little to change the course of human history in the way that he and nearly everyone else on Earth at the time expected it to. I wish desperately that the United States and other countries would put more emphasis on space exploration and colonization, so that the efforts of the Apollo astronauts won’t have been in vain, and so that we may explore and experience a better portion of the universe that God created for us, as He intended.